On 8 December 2016, six students from Melbourne, Monash and Deakin Universities debated West Papua’s status as an independent state. The exhibition debate was hosted by the Federal Republic of West Papua (FRWP) in the Australia Catholic University during the Sampari Art Exhibition for West Papua. The debate was moderated by DR JONATHAN BENNEY, President of the Debaters Association of Victoria and lecturer in Chinese Studies at Monash University.

The Melbourne University Debating Society, arguing against West Papua’s independence, was represented by BEN O’SHEA, ZOE BROWN and ALESSANDRA CHINSEN. The affirmative team, arguing that West Papua was well prepared to sit amongst the nations of the world as an independent Melanesian state, was led by KELVIN KA WING NG from Monash University’s Association of Debaters, and JOYCE LI and REBEKAH DE KEIJZER from Deakin University.

MONASH ASSOCIATION OF DEBATERS [MADS] and MELBOURNE UNIVERSITY DEBATING SOCIETY [MUDS] with Dr Jonathan Benney and Lance Collins (Photo-Tommy Latupeirissa)

After the debate questions from the audience were fielded by BISHOP HILTON DEAKIN, LANCE COLLINS, DRS JACOB RUMBIAK and ISAAC MORIN. Bishop Deakin is Patron of the Australia West Papua Association (Melbourne) and an influential observer of the important role of Churches and activists in political change. Lance Collins, formerly Lt-Col Lance Collins, was head of INTERFET (22 nations) military intelligence in East Timor between September 1999 and February 2000. Jacob Rumbiak is Executive Officer of the United Liberation Movement for West Papua and FRWP Minister of Foreign Affairs, Immigration & Trade. Isaac Morin, also from West Papua, is completing a doctoral dissertation on Melanesian identity at La Trobe University.

The debate was of a high standard, and well supported by an informed audience that included O’Conroy Doloksaribu from the Indonesian Embassy in Canberra, and Oldrin Lawalata from the Indonesian Consulate in Melbourne. A global audience was able to participate in real time on Facebook. An informal survey of the local audience suggested that if Melbourne University didn’t actually lose West Papua for Indonesia, the Monash-Deakin team presented a convincing case of the former Dutch colony’s willingness and capacity to over-ride Indonesian colonialism.

Media Interview with Jacob Rumbiak before the debate [click to play]

LUNAR FLARES a composer-performance trio from Footscray opened the evening with an edgy performance of an ethereal soundcape punctuated by vocalisations of the text “No war, Lay down your sword of defence, It has no use, What are we fighting for? There’s no war in my home”.

Video of Lunar Flares opening Sampari Art Exhibition [click to play]

Babuan Mirino, FRWP Womens Office, Opening the debate [click to play]

Babuan’s Welcome Speech: “Mandira Bebye. Good evening, and welcome to tonight’s debate. My name is Babuan Mirino and I am President of the West Papua Womens’ Office in Docklands. It’s wonderful to have Australian future leaders interested in our future and I congratulate Melbourne and Monash universities. I feel very happy to be here at the Australian Catholic University surrounded by this amazing West Papua art. On behalf of all West Papuans, here and at home, I thank our brothers and sisters, the Wurrundjeri people, for letting us use their land today. Now, let’s welcome Dr Jonathan Benney to moderate the debate.”

Edited transcripts of the debate

[click to] JONATHAN BENNEY Introduction

[click to] KELVIN KA WING NG 1st Speaker Affirmative

[click to] BEN O’SHEA 1st Speaker Negative

[click to] JULIE LI 2nd Speaker Affirmative

ZOE BROWN 2nd Speaker Negative [removed at request of speaker]

[click to] REBEKAH DE KEIJZER 3rd Speaker Affirmative

ALESSANDRA CHINSEN 3rd Speaker Negative [removed at request of speaker]

[click to] JONATHAN BENNEY Reflections on the debate

[click to] AUDIENCE QUESTIONS TO EXPERT PANEL

Dr Jonathan Benney, Introduction

I’d like to offer my thanks to Babuan, to the band that just played, and to everyone who has made this night a possibility. I am here in two capacities. I work at Monash University as a lecturer in Chinese studies so I am confronted with issues relating to Asia every day. I am also President of the Debaters Association of Victoria, a large non-profit organisation that facilitates debate particularly in secondary schools. So I’m here to facilitate and explain the debate that is going to take place tonight about the independence of West Papua.

Before I explain the format, I will introduce our EXPERT PANEL who will answer questions after the debate. From West Papua we have JACOB RUMBIAK Minister for Foreign Affairs of the Republic of West Papua and Executive Officer of the United Liberation Movement for West Papua; and ISAAC MORIN who has nearly finished his PhD at LATROBE UNIVERSITY concerning West Papua. Both these people understand the issues around implementation of an independent state, and how West Papuans feel about the current situation. We also have BISHOP HILTON DEAKIN, Patron of the Australia West Papua Association (Melbourne) who for a very long time, including in East Timor, has been an observer of the church and activists in the process of self-determination. Finally we have LANCE COLLINS who was the head of INTERFET military intelligence in EAST TIMOR under General Cosgrove in 1999—2000. His historical novel A DOWRY FOR THE SULTAN which demonstrates the breadth of his talents explores relations between Muslims and Christians in the eleventh century.

Our debate is on the subject of whether West Papua should be independent or not. We have two sides: the affirmative side will agree with the idea that West Papua should be independent, and the other side will oppose the motion. Each side has three speakers, who will speak alternatively, each for seven minutes. Before introducing the debaters I should stress that the sides were allocated randomly, and that the opinions put forward as part of this debate are not necessarily the opinions that each speaker holds. They’ve been allocated a side, and will argue their hardest for that side without necessarily reflecting their own personal beliefs. That’s a very important part of the process of debate, and I think that’s actually a useful process that encourages people to think outside their own personal beliefs and reflect on key issues.

For the affirmative side supporting the independence of West Papua, we have one speaker from Monash University and two from the Deakin University Debating Society. Our first speaker will be KELVIN KA WING NG a Commerce Law student at Monash who will be representing Monash University’s Association of Debaters at the WORLD UNIVERSITY DEBATING CHAMPIONSHIPS in the Netherlands at the end of this year. Our second speaker is JOYCE LI who is a law student at Deakin University, and our final speaker is REBEKAH DE KEIJZER, an international studies and law student and President of the Deakin University Debating Society.

The negative side are all students from Melbourne University, representing the Melbourne University Debating Society tonight and at the World University Debating Championships in the Netherlands. Our first speaker is BEN O’SHEA who is a second-year student in the Juris Doctor program, the law-degree program at Melbourne University, and Vice-President of the Debaters Association of Victoria. The second speaker is ZOE BROWN who has completed an arts degree and will be starting law next year. She was one of the coaches of the schools debating team that represented Victoria at our state debating championships earlier this year. Our third speaker is ALESSANDRA CHINSEN, an arts student who is very interested in international development.

[click for PDF of full transcript] debate-transcript-welcome-dr-jonathan-benney

Kelvin Ka Wing Ng, 1st Speaker, Affirmative

Audience, the West Papuan struggle for independence has been a long and arduous one, with many people being imprisoned, tortured and even killed in the process. Despite this the West Papuans have continued fighting for independence. Why? Because they believe that freedom is something that is worth fighting for. And that is something we are very proud to stand behind. I’m going to be doing four things in this speech. Firstly, providing a bit of the historical backdrop. Secondly, explaining what we see as the path to independence. Thirdly, explaining why West Papua deserves independence. And finally explaining the practical benefits thereof.

So beginning with the historical context. Prior to Dutch colonisation, West Papua was a traditional tribal society for the most part. With Dutch colonisation came the inculcation of Christian values through missionaries. In World War 2 we saw that West Papua was a vital battleground in the Pacific for the Allies, and after World War 2 there was a movement towards independence under the Dutch, but this was opposed by Indonesia who wanted to claim sovereignty of this territory after itself having recently been freed of Dutch colonialism. Indonesia’s efforts were supported by the United States at the United Nations—given the wealth of resources that existed in West Papua. So transitional power was then given to Indonesia and then ratified by the Act of Free Choice in 1969.

Since then West Papua has been governed by Indonesia, and has been partitioned into two sections. Special autonomy was introduced but has failed due to poor implementation. In terms of movements towards independence, there have been the Forum Reconsiliasi Rakyat Irian, and the Presidium, and more recently by the Federal Republic of West Papua, National Parliament of West Papua, and West Papua National Coalition for Liberation, as represented by the United Liberation Movement for West Papua. We see that they have moved along the path to nationhood, including a declaration as a state, and they have received international recognition from the Melanesian Spearhead Group and the Pacific Island Forum.

We propose a continuation of this non-violent approach to political change that embodies both traditional Papuan and Christian values. This approach has been effective elsewhere, such as Mahatma Ghandi’s movement in India. What we support specifically are grass-roots activism, a push for greater international recognition by bodies such as ASEAN and the UN Decolonisation Committee, renegotiation of resource contracts with US companies, and a peaceful transition of power to the West Papuan people under a West Papuan government.

We think there are two principle reasons why West Papua should be free. Firstly the process of acquisition of sovereignty was flawed. Only one-thousand of the approximately 700,000 West Papuans were permitted to participate in the Act of Free Choice and all of them were coerced into saying ‘yes’. Secondly the acquisition of rights over minerals was also flawed. The resource contract was drawn up and signed before the Act of Free Choice, which means they were giving away property that didn’t belong to them. There was an asymmetry of bargaining power in that the state at the time had only recently come out of colonialism itself—as exemplified by the split of profits with 90% going offshore, 9% to Indonesia, and much later 1% to West Papuans.

But we think that another perhaps more compelling reason is the injustices suffered by the West Papuan people. The civil rights abuses that have occurred at the hands of successive Indonesian governments have attracted international condemnation. As stated already, people are imprisoned, tortured and killed in efforts to suppress political dissent. We think there has also been an exploitation of the resources in West Papua. We believe that the United States (that derived benefits during World War Two when many West Papuans fought and died on behalf of the Allies) has indirect responsibility for the human rights abuses occurring under Indonesian in that it facilitated Indonesian control by supporting UN resolutions in 1962 and 1969, and fought a proxy war in Indonesia during the Cold War by giving the young republic a mandate to fight communism, which was then usurped and used to further suppress political dissent. Finally we think they exploit the resources in the area through a foreign directed company.

As such, we think the West Papuans having suffered so much are entitled to a right to self-determination. This is well enshrined in international law, including the Declaration of the granting of independence to colonial countries and peoples and the Declaration of the rights of Indigenous peoples. It is also consistent with Indonesia’s development path, in that Indonesia having been delivered of Dutch colonialism has a constitution which proclaims ‘independence is the inalienable right of all nations and therefore all colonialism must be abolished’. We believe Indonesia’s occupation of West Papua as a modern-day form of colonialism.

Moving onto the practical benefits. We see the key stake-holder being the people of West Papua, and we think that as a general rule self-determination is going to benefit the country, in that it’s government by the people for the people, where the interests of the people on the ground are more likely to be served, as opposed to a situation of moral hazard, where they are not directly affected, or worse a situation where you are able to benefit by exploiting the people of West Papua, which is what we believe is occurring under the status quo.

Politically we think the West Papuan people currently have a limited political voice, whereas under our model greater international recognition would bring with it a platform to advocate for their interests.

But in terms of human rights. It is actually quite hard to get information about what’s occurring in West Papua as the Indonesian Government has suppressed the media, has kicked out missionaries, and prevented UN fact-finding missions from entering West Papua. Under these conditions we think it is probably fair to say it is because the information wouldn’t be favourable to them. What we think is that greater international recognition would make it harder to kick the media out, and the media could serve as a source of accountability. But we also believe that the incentive for oppression under the status quote and the abuse of human rights is to prevent West Papua becoming a separate state. Once that occurs the incentive will no longer exist.

Demographically we have some things to say. West Papuans are ethnically and culturally distinct being predominately Melanesian and have Christianity as their main form of religion in addition to some traditional tribal beliefs. Whereas Indonesians are majority Asian and Muslim. There has been a huge decrease in the proportion of Melanesians, due to deaths, migration and an agenda of Islamization. We think that this Indonesian concept of a unitary state is unsustainable given the size of the population and cultural differences within it. What we believe is that having control over their own borders would allow West Papuans to prevent cultural erosion.

But finally we see there are some economic benefits under the status in that despite being one of the most resource-rich areas in the world, West Papua is the second poorest Indonesian district. This is because the wealth is being transferred overseas, so we think the would be better able to negotiate a more equitable distribution if they had their own sovereignty.

In conclusion I will borrow the words of Lech Walesa who fought for workers rights in communist Poland. “We hold our heads high, despite the price we have paid because freedom is priceless.”

[click for PDF of full transcript] Debate, Transcript, Kelvin Ng

Ben O’Shea, 1st Speaker, Negative

As much as principles like sovereignty and self-determination are important, and as problematic as the Act of Free Choice was, we think it’s more important in this debate to look practically at what West Papuan independence may look like in the short to medium term. I’m going to discuss each of the pathways towards independence that are available at the moment, and explain why each of them in their own way are to some degree problematic. You’ll be hearing from Zoe about alternative pathways for the future of West Papua which could help to improve human rights and improve representation, but still operate within the framework of Indonesian governance.

So what pathways are actually available for West Papuan independence? We think it’s really important in this debate to acknowledge that Indonesia does not support West Papuan independence, and under no circumstances at the moment is willing to allow that region to separate and become an independent country. We’ve seen that played out again and again in terms of cracking down on rebel groups and other measures like that.

We also think it’s important to realize that there isn’t a great deal of international support for an independent West Papua from the international actors that matter in terms of being able to place pressure upon Indonesia to change their actions or being able to provide international recognition through international forums. Australia for instance signed the Lombok Treaty in 2006 with Indonesia, which explicitly recognizes Indonesia’s sovereignty and territorial integrity, and explicitly agrees not to recognize separatist movements. We’ve seen that play out even further in recent months with Australia pressuring other Pacific states not to pursue their support of West Papua’s independence. That’s something that is in Australia’s interests to follow through, given the cooperation that is often requested in terms of dealing with border security and other issues.

It’s similar for the United States where the US-Indonesian Comprehensive Partnership is based primarily upon respect for Indonesia’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. If we look at a number of Asian countries, we see that many are signatorees of the Bangkok Declaration, which explicitly recognizes the sovereignty of other signatoree nations and their right to put their sovereignty and economic development ahead of civic and political rights. Many of the economic powerhouses of the region, like China, Japan, Korea and Indonesia, are signatorees. Other regional actors, like Taiwan, Malaysia and Vietnam, have explicitly agreed to recognize and respect Indonesian sovereignty. So none of these states have any sort of incentive to recognize West Papuan independence. That the Pacific Islands Forum provides some sort of recognition is to some degree important, but the Forum doesn’t have the ability to put trade sanctions on Indonesia, or withhold aid and other financial support. So we don’t see in the short to medium term a political climate that is conducive to placing pressure upon Indonesia to recognize independence.

We also believe that revolution isn’t currently in the pipe works. At the moment we see many independence groups disarmed, with no large military structure or resources in place to throw out any sort of Indonesian presence.

But let’s set all that aside for a moment. Let’s consider that were West Papua to become independent, what are some of the problems that would still exist and need to be addressed. We think firstly and most importantly there is the recent issue of transmigration, which now means that roughly fifty per cent of the four-and-a-half-million people in West Papua are not members of the traditional Melanesian population. Rather they’ve immigrated there, or are recent descendants of people from other areas of Indonesia. So the question becomes what happens to those more than two-million people who are now in West Papua if it is an independent state?

A couple of options are available although neither is attractive. The first concerns re-location. We think that trying to re-locate two million people after taking away one-fifth of Indonesia’s landmass would be hugely problematic given there are already two-hundred-and-fifty million people living in the region. But if you were to allow the Indonesian population to remain, with full democratic participation, West Papuans would end up an ethnic minority in their own country. Alternatively if you were to set up special provisions and representation for ethnic West Papuans, you have the problem of creating an under-class of citizens with limited access to the civil service and education and other resources. That’s what we’ve seen play out in Malaysia, which prioritized certain ethnic minorities over other particular groups. Furthermore you also increase any justification by Indonesian for intervening in West Papuan affairs, as Russia does with Crimea, sending military forces in, or interfering with foreign affairs because ethnic members of its community don’t have equal rights and equal protections. So allowing the Indonesian population to remain in West Papua is hugely problematic.

We also know that there is likely to be an economic detriment to an independent West Papua. We know that new states often have a poor ability to attract foreign investment. And the reason for that is that when foreign companies move into a country they know that they are operating within a particular political framework and a particular legal and taxation framework. And that doesn’t exist in West Papua at the moment. Foreign investment is necessary, not only for bringing in revenue, but also for creating job opportunities and infrastructure development. For instance, we would worry that West Papua independence would jeopardize the sustainability of the Grasberg mine, which is the world’s largest gold mine and third-largest copper mine. At the moment under the Special Autonomy Law eighty per cent of taxation revenue from the mine stays within West Papua. The ability to go off and implement a taxation regime is necessarily reduced when you remove the Indonesian influence from that area.

On the negative team today we are not against principles of sovereignty and self-determination, but we do think it is important to look up the practical consequences and what is lost out when you remove the framework that the Indonesian government already has in West Papua.

[click for PDF of full transcript] debate-transcript-ben-oshea

Julie Li, 2nd Speaker, Affirmative

The opposition today wanted to speak about the feasibility of West Papuan independence, of how there isn’t support neither from Indonesia, nor from other states. Well I will prove to you why there are incentives and reasons for Indonesia to support West Papuan independence, and that nations have already started to move to recognize West Papua’s independence.

We think that in terms of the environment, there can be analogies drawn between the importance which Melanesians place on their connection to the land and the relationship between indigenous Australians and their land. Both are different from the Indonesian-Asian connection to the land, and we think that’s another reason why West Papua should be independent.

We see that in terms of social cohesion, there are in West Papua, as in any other nation, disagreements between groups. We can see that between the tribes of the highlands and the tribes of the lowlands. However, we believe that identity and social cohesian will be strengthened when West Papuans can move freely and champion the cause of their own independence.

I’m going to be talking about the feasibility of West Papua’s independence in two sections. Firstly, the legal feasibility, and secondly the practical feasibility. Under practical feasibility, I will tell you how we can convince Indonesia and other states and foreign corporations to support West Papuan independence. I will also address governmental expertise and economics.

So let’s talk about legal feasibility. West Papua has already declared independence. The Montevideo Convention states that three pre-requisites for statehood: territory, population, and governance. We believe that West Papua meets all three elements of this convention that codifies statehood in terms of international customary law. In addition to having a governmental structure, as represented by the United Liberation Movement for West Papua, the state of West Papua has the capacity to enter into relationships with other institutions and other states. We can see this in its relationship with the Melanesian Spearhead Group, as my first speaker mentioned, where West Papua currently has Observer Status and will soon be granted and promoted to full status. We think that this is a positive move in the right direction to gaining independence and recognition within major platforms such as the United Nations.

Now let’s talk about the practical feasibility. The opposition claims there is no way that Indonesia would support West Papuan independence. That is a common assumption, but when we look at the actual incentives, we can see that it is quite burdensome for Indonesia to have its administration and its military suppressing the West Papuans who yearn for freedom. We think that it is a massive cost in comparison and in proportion to any benefits that Indonesia derives. We can also see the cost of Indonesian contracts with US corporations where there is a 91—9% split in the profits. We think that 9% profit is far outweighed by the costs.

Secondly in terms of social cohesion, we see that Indonesia has other provinces, like Aceh, that are also pushing for freedom and independence. We think that this is stressful for Indonesia and intensifies the fractitious relationships within Indonesia.

Thirdly, we think that in terms of international reputation, Indonesia will suffer a back-lash, with consequences such as sanctions. We can see the harsh economic consequences on Russia after hey annexed Crimea. We believe national pride and the reputation of Indonesian politicians will suffer. We saw that when there was a massive outrage in Australia over East Timor’s independence. What happened there? There was a UN intervention.

Now to governmental expertise. Right now there is in West Papua viable governmental structures, comprised of experts, intellectuals, and academics, who have had governance experience, who are going to support the move to independence, and who are going to govern West Papua when they succeed. These administrations are already functioning. They have been acknowledged by the church in West Papua and their ambassadors are developing relations with state governments, and with universities such as the ACU. We believe this signifies there won’t be a void during West Papua’s transition to independence. In other words, the self-determiantion movement is set up so that it will succeed.

Finally, to economic feasibility. We think, despite the opposition claiming there won’t be any foreign investment because the economy isn’t as big as Indonesia’s, that West Papua is a resource-rich country, from which revenue can be generated that can be used as security against loans from other nations to fund industries and infrastructure such as schools and universities. For all these reasons, we believe the opposition’s arguments about how West Papua’s independence was unrealistic or not actually feasible are wrong.

[click for PDF of full transcript] debate-transcript-julie-li

Zoe Brown, 2nd Speaker, Negative (transcript removed at speaker’s request)

Rebekah de Keijzer, 3rd Speaker, Affirmative

Audience, what we think our opposition has failed to understand today is that the world as we know it is changing around us. Treaties can be revoked and rewritten. Incidences of human rights abuses can be recorded and put on social media and circulated throughout the world within seconds. Governments and nations can be built. What doesn’t change however is the right that every single individual has to self-determination and self-governance. And that is the right that we on the affirmative team are so proud to stand behind in this debate today.

What I see this debate come down to is two main things. The first one being the feasibility and the potential success that West Papua would have as an independent nation. And the second is, what is the best pathway for the West Papuan people. Is it independence, or is it any other pathway that we can use as an option?

On the idea of the feasibility of West Papua as an independent nation, we would like to remind our opposition that there is already a West Papuan government. In their struggle for independence they have forged their own government. They have viable structures that can be put in place if the Indonesians withdraw. We think this is a functioning acknowledged government that is already an oiled machine and is ready to go.

Secondly, on the idea of how successful this country would be as an independent state. We all know about the wealth of West Papuans natural resources. We think that because of this wealth and because of their right to sovereignty, they should be allowed to choose what they want to do with their own resources, including bringing in revenue to build their own infrastructure and forge their own nation. This is so important and at the very heart of this very struggle and debate.

In the independence struggle we have seen wonderful things come out of the West Papua people. We see a strong national identity. We see a community that sticks together. We think that all this just evidences the fact that West Papua would be able to function as its own state and would be a very successful one at that. Their own state would be viable and could be economically successful and sustainable on its own without Indonesia’s influence.

Another idea within this debate what is the best approach for the West Papuans? What’s going to bring the best result? We are advocating for independence, because despite what the opposition likes to claim, we don’t really think there is an alternative approach. We think that at the heart of the struggle, and of every single West Papuan, they want to have their own self-determination, the right to decide what kind of governance they would like, and what kind of rule that would be.

We’d refer you to East Timor where we saw a huge public outcry in Australia because of human rights violations which led to an Australian-led UN intervention. We think that is a clear example of how it would be feasible for West Papuans to gain their independence, through independent parties recognizing what’s going on and pushing for positive change towards self-sovereignty.

On the idea of how Indonesia would react to this. We think that there actually is a lot of support for West Papuan all around the world. We see groups like the International Lawyers for West Papua. We see many people here today who do have this cause in their heart. We think a lot of people sympathize with this cause. And we think that this sympathy will lead Indonesia to understand that we live in a very globalised world and a nation’s reputation matters when it comes to global trade. We believe that provides an incentive for Indonesia to want to give them their own governance. Also social media is having more and more of an impact. We think that’s why Indonesia, which is already a fractitious country, would be looking towards independence as a viable solution for many of their problems.

The idea of the Melanesian Spearhead Group, which has recognized West Papua, would also be an important driving force for independence, and would propel West Papuans to have their own nation-state and sovereignty. We think this movement will grow through independent observers understanding what’s going on, seeing the struggle and the passion that West Papuans have for their own self-determinacy, and we think that is why a peaceful path towards independence has always been possible, and why we are always happy to propose on the affirmative side.

The idea that there is an alternative pathway to independence is not an idea that we support at all. We think that without sovereignty there will always be oppression of human rights. There will always be oppression of culture. West Papuan’s resources will always be exploited. We think independence is the only way to counteract these harms and move towards a better future. We don’t think Joko Widodo’s presidency is actually good for West Papuans at all, despite the opposition’s claims, and we think the end goal is always independence. This is what the grass-roots in West Papua is striving for and is in the heart of every single West Papuan.

So audience I put to you that the UN and other global powers are no longer able to ignore the oppression of the West Papuan people, and that independence is the only answer to counter these decades of struggle and decades of harm perpetrated against West Papuans. We see that the West Papuan people, who have the most to lose in this conflict, have never given up in their struggle and have always strived for independence. Through their struggle they have formed a strong national identity and strengthened in their resolve as a community. They want full freedom and nothing less. Ladies and gentlemen, in the context of this debate, independence for West Papua is and can be the only answer.

[click for PDF of full transcript] debate-transcript-rebekah-de-keijzer

Alessandra Chinsen, 3rd Speaker, Negative (transcript removed at request of speaker)

Dr Jonathan Benney, Reflecting on the Debate

Thank you very much. I am going to spend a little time talking about the debate, focussing on all the techniques and structures and skills that make up a debate. And then I’m going to put my academic hat on and look at some of the issues brought up in the debate.

I’m not here to say which side won the debate although we often do that when we are judging debates. But I do want to reiterate—I think it’s important to do this personally and on behalf of our organization, that I echo what the negative team said, that regardless whether West Papua can or should be independent, we all should stand in solidarity with the identity culturally of West Papuans and the struggles that they’ve gone through and the harms that they’ve suffered at the hands of colonialists. I do want to stress that because I believe it’s important to start with.

Durng the past twenty or thirty years, debate has exploded in popularity across Asia. In Singapore where I used to live, in Indonesia, right through to Papua, in authoritarian or post-authoritarian countries like China, Korea, or Malaysia. Every country on the map except North Korea has a debating program in which students and young people debate in English or in their own languages. That has been a tremendously interesting and important phenomenon across the whole of Asia, because it means that people in all different types of societies, under all different types of political systems, and from all different backgrounds can voice their views on what are very tough, very controversial, very sensitive, very difficult issues, and hear both sides in a complicated but fair way. So I think the growth of debate in Asia is a terrific phenomenon, and when the speakers from both sides head to the World University Debating Championships next month, they will see and quite possibly be beaten by universities from Asia. I think that’s a wonderful phenomenon and it’s one of the reasons I continue to be involved in debate.

We look at three things in debates. One is what the speakers say, their content. The second is how they present their content: how they speak, and gesture, and look at you and so on. The third thing is how they organized themselves within their own speeches and as teams. I think that in this debate we saw lots of strengths. We saw different styles of speakers. Each speaker spoke differently but in very confident and very effective ways. There was lots of information crammed into the debate, but expressed in interesting and engaging ways. Both teams listened to each other and took into account opposing views, and for those reason I think it was a strong debate. I think the debaters performed very well tonight and I hope you enjoyed listening to it.

But I want to talk about some of the issues in the debate, concerning questions not just applicable to West Papuans’ independence, but also to other nations, or potential nations, or cultural and ethnic groups, not just in Asia but across the world. These are issues that we will see in all sorts of debates, and issues that are very important to be able to think about.

The first concern is the idea of a unitary state. Is it more viable to have giant states? My expertise is in China, where there are separatist movements. It’s the same in Indonesia. Arguably we could say it takes place in Australia, or Canada, or Brazil, or any of the other large unitary states that we have. And this brings up a big question. Is the unitary state politically and socially more viable than smaller independent states? Is it more ethical? Does it better facilitate things like human rights than the unitary state? We heard both sides of the argument tonight. We have these big unitary states because of our colonial legacy. So how do we deal with the harms of this post-colonial legacy? What is the best way of responding to these harms? And how do nations or communities or individuals or smaller groups engage with these harms?

We heard from the first speaker that one of the best ways of responding to the colonial harms visited on West Papuans was for them to become an independent nation. But that provokes an interesting question: will West Papua or can West Papua erase these harms, or deal with these harms, or limit these harms by becoming independent? Will West Papua be sufficiently united to achieve its aim of freedom if it’s independent? Does West Papua actually need to be a state to achieve its aims of autonomy? These are some of the questions that the negative team brought up. What about the ethnicity of West Papua? Is West Papua ethnically coherent enough to become an independent nation, and does that even matter? Does it matter if an independent West Papua is ethnically diverse? Or will it be harmful to West Papua, if as the negative team suggested, the legacy of transmigration remains. Will West Papua develop a sufficient cultural and national identity that will help it move forward as an independent nation? Or is it a complex diverse nation, where we should just group everybody together as being, say, of a Melanesian culture, when in fact there are many different tribes in different locations. These are all questions that we can’t answer but are crucial to ideas about geo-politics.

The second issue is principles versus practicalities. From the affirmative side, we heard about broad principles: freedom, sovereignty, self-determination, connection with the land. It was very powerful, I’m sure you’ll agree, when the affirmative team brought up these notions of freedom; it is something that appeals to us emotionally and in some ways philosophically. The negative team didn’t disagree with these principles, but they talked about how they could be facilitated. Would West Papua be politically and economically successful? The affirmative team told us that there were enough resources, both natural resources like the mineral wealth and human resources like the potential government. But then the negative team pointed out many small problems. I don’t think there was one single problem that the negative team brought up that on its own meant West Papua couldn’t be independent. But if we took all of those small problems together, perhaps they call the idea of West Papua independence into question.

The third issue is, where would West Papua fit into the global world? It was an assumption of the negative side that global recognition of West Papua was crucially important to its sovereignty. There are examples that support that in our global world and there are examples that don’t. If we look at Taiwan, for example, where I am going to spend some of my time next year, it is a nation with very little international recognition, but a high level of political and geographic coherence and a great deal of sovereignty. Does recognition matter all that much? How can we tell? How would West Papua fit into the global and regional network? Should we consider West Papua part of Asia, Melanesia, Pacific, or a global community which isn’t linked by geographic regions at all? It was very difficult for either side to explain how West Papua would fit into the geo-political scene.

And that brings me to the fourth issue: what would be the consequences of West Papua becoming independent? How would people react? How do we know how people would react? Both sides had to look into a crystal ball here. The affirmative side said that everything is ready to go, West Papua is rich in natural resources and rich in human resources, and it’s a coherent nation, and on the whole everything will be fine. They provided lots of evidence and in some ways that evidence was very plausible. The negative team said the future will be very different: that Indonesia would react negatively, that there will be a violent protracted conflict, and this would be very harmful to West Papuans. There are a few things I could say about this, but I will speak very briefly. We know that Indonesia would react, but as for how Indonesia would react, and the form the reaction would take becomes speculative and unclear. While the negative side provided lots of information, I don’t think I left the debate feeling absolutely sure that I knew that that would happen.

Then there was the question of an alternative. Is there some kind of intermediate path to independence that might include greater sovereignty and greater autonomy? The negative team suggested things were changing in Indonesia and that West Papua was likely to get greater autonomy. If we accept as true what the negative team sad, there is less risk of violence and it might be easier for West Papua to become independent. So that argument is not necessarily water tight. But then there’s the question of how the global community would react. Would anybody defend West Papua if there was war? How do we know, and how can we tell? We had conflicting evidence from both sides here, and I think it would be very difficult to adjudicate.

So these are four issues: What’s the role of the unitary state? Are principles more important than practicalities? How do nations in our global world fit together? How important is sovereignty? And what happens, and how do we predict what happens after a nation declares independence? These are all crucial geo-political questions. These are all questions that we could apply to Tibet, Jinjian, or Crimea, or Taiwan, or other parts of Indonesia… the list is almost infinite.

What I’d like to now handover to people who really do know about West Papua. I don’t say that to criticize the debaters … I think thanks to Louise and the West Papuan community, they’ve learnt a lot about West Papua, and I’m very impressed with that. I can’t claim to be an expert on West Papua either, so I invite questions from the audience to our expert panel. You can direct your questions to specific people because we have Jacob Rumbiak and Isaac Morin, and Bishop Deakin and Lance Collins. I for one would be very happy to hear their opinions.

[click for PDF of full transcript] debate-transcription-reflective-comments-dr-jonathan-benney

Audience Questions to Expert Panel

Q: Bishop Deakin, how is Australia implicated in this situation?

BISHOP HILTON DEAKIN First of all I’m not an expert on this at all, but I am an observer of what goes on. I have never been to West Papua except from the other side in Papua New Guinea, and got out again fairly quickly. But I have spent many years in East Timor so I have a very certain taste of the processes that go on. Now if I may say so I enjoyed this debate. I won’t say anything about the man who is making it all possible, but keep it up.

The first thing I want to say is, Don’t let us tell the West Papuans what they should do. Let us discuss it. Let us see it if we want it as a problem for Australia, for the West Papuans, for the Indonesians, and for anybody else. But somehow or another let the West Papuans be the people who want to tell us what they truly want. And you won’t find that by just asking Jacob because he’s only one of them. You’ve got to listen. Listen, listen, listen. And talk. Read of course, and discuss, but don’t come up with solutions. The solutions have to be what the West Papuans want. I make that as the first point that I really want to make.

I want to make another point before I get to this comment about Australia. I think one of the most important features about what is going on in West Papua—not the only one, but a most important one—is the economic factor. None of the debaters said, for instance, that at the western end of New Guinea there is more oil and gas than there is in the Timor Sea. Nobody ever talks about it, but the Indonesians know about it, and they are building ports and arranging facilities for refining and all the rest of it. Now that is the inheritance, if I may eulogize in a way, that nature gave for the West Papuans to have to build their own nation if they want to.

Another thing is that West Papua has one of the richest forest areas in the world. And guess who’s woken up to it? I think the Indonesians have, they’re not stupid at all, but the Malaysians are the people that are picking the eyes out of it. Not too much is being said, but that’s being taken away from the West Papuans as well. If you are going to have the sort of state that requires the jobs and the growth Mr Turnbull and others in this country talk about, you’ve got to have these natural resources to build on.

I used to teach anthropology at university, and I think the cultural matrix that’s in West Papua has to be very carefully understood if you want to understand what the needs of the people are and what their desires and wishes will be. Don’t give them a western one, and particularly don’t give them the hollow one that the Australians reckon they can give. So those are my three warnings.

Now in terms of Australia: what I have experienced over twenty-five years going into East Timor every year for a month or so, is that Australia has got a dreadful reputation in East Timor. Don’t believe what you read in the papers. Don’t believe John Howard. That was all a game. Peter Cosgrove didn’t fire a gun except at some of his own soldiers who were disobeying him. The East Timorese went through hell, and they are still picking up bits of bones. When I went in there a week after the end of the war and visited places like Suai and Same, I walked through fields three times as big as the MCG and all I could see were bones. Smelt corpses and blowflies. Hundreds of people who’d been put to death; shot and then tried to be burnt. This was part of the heritage, and it stays with you until you breathe your last. And it will happen also with the West Papuans if things turn out that sort of way. They are the sort of things that require the wisdom of the ages, and also especially I think, humility; to see these people as our brothers and sisters with whom we can work. If they want freedom, yes. If they don’t want freedom, tell us what they want. I have no idea, maybe peace and happiness in a tribal setting … one has to go there and find out and ask the experts on all these sorts of things.

Australia has a very bad, sad, and rotten record with East Timor. I’m fighting in a small way for changes to the maritime boundary between Australia and East Timor. You know, throughout the world, except in Australia, maritime boundaries are straight lines right through the middle. It’s not law, it’s an international practice that has been sanctified because it has happened so often. But Australia won’t do it. They have a boundary that goes something like this, and guess what’s in that area? The oil and the gas that is East Timor’s but which is coming to Australia. Of course, Australia says ’We’ve been very generous with you East Timorese people …we’ve got forty million out of that basin, and we’ve given you four.” But the forty million should have gone to East Timor, the whole jolly lot of it. I’m deeply ashamed when I go to various meetings to discuss this. I am ashamed to listen to the top political figures in this country talking about foreign affairs and the maritime boundary between Australia and East Timor. Believe me, if that’s the way it’s been for the last twenty years, it’s going to be similar when it comes to West Papua, because that’s the only example we’ve got. So we’ve got to think, and re-think all of this and develop a sensitivity and a maturity that I don’t think exists at the present time.

BISHOP HILTON DEAKIN, Patron, Australia West Papua Association (Melbourne) Photo-Tommy Latupeirissa, 8 December 2016

Q: Lance, has West Papua got a chance in hell if they decide to take the military path?

LANCE COLLINS I want to pause on that question for a moment because I’d like to thank and congratulate the debaters. That was a splendid performance. Well done all around. My only comment is that if you are addressing an international audience you might slow down the delivery, because Australians tend to speak quickly, and even more quickly when we are under pressure—except a former prime minister who had trouble getting words out when under pressure.

I also want to talk a little bit about the independence of East Timor. That happened at a moment in time. For the twenty-four years of the Indonesian occupation from 1975, there was a veil of secrecy drawn over East Timor. Two states in particular were complicit in that. One was Washington, Washington being separate from the American people; and the other one was Canberra, Canberra being separate from the Australian people. And what brought down that three-ways agreement to continue the Indonesian occupation of East Timor was the Asian financial crisis of 1997. That shocked a number of Asian countries, starting with the Thai baht, and then went on to the Indonesian currency, and staggered the entire Indonesian system. And in that moment in time the East Timorese resistance was capable enough and organized enough, and had a foot in the door at the UN where they were able to give the push for self-determination a big shove. And because they had that window of opportunity it actually worked.

For some of the questions raised tonight about how a move to independence or self-determination would go, I was a witness and can attest to the very remarkable goodwill of people from a huge range of countries under UN auspices that did their best to make it work. I echo the Bishop’s comments about Australia’s risable arguments over the seabed boundary with East Timor, but internationally, when there is a moment in time, the international community will step up to the plate on the issues of human rights and self-determination.

West Papua is also a situation in time. When it was originally occupied by Indonesia the world population was something like three billion. It was at the height of the post-World War 2 rise of capitalism, which has now gone on unchecked for seventy years, even if the strains are beginning to show. We’ve had one global financial crisis, people say others are coming, and the results of upset are indicative of what could happen. However, just as no one saw the 1997 crisis coming and the affect it would have on Indonesia, no one can really predict what is going to happen internationally in the future.

So for West Papuan self-determination, the opportunity could come and be fleeting. The record of death speaks for itself. 183,000 killed in East Timor, either killed or died of malnutrition or famine. No one really knows the number of people who have died in West Papua, but the figures range from one hundred thousand which seems conservative, up to half-a-million.

Any sort of out-and-out war there would be very bloody. But the key to it is to keep on with, I believe, the non-violent resistance, because with the advent of the internet and a more globalized counterculture rather than a corporate culture, we are starting to see successes; in Standing Rock, the stand-off in the United States at the moment between Native Americans and corporations over a pipeline, and in countries like Papua over traditional lands.

So the future is hard to predict. Two points that I would want to make. The resort to arms would be a last resort because it would be bloody, particularly without international humanitarian intervention. The second point is that on human rights and self-determination alone, when the opportunity arises, the world will step up to the plate. Thank you.

Q: Isaac, I’d like to hear a bit about the autonomy process. Because my observation was that although it’s promoted to help give West Papua some form of independence, it really has been a process of indonesianization especially as it’s been associated with the transmigration. I think we need to know something about that, and the failure … well not only the failure but the deliberate policy that promoted this autonomy but was really something very different.

ISAAC MORIN Thank you. First of all I would like to thank the debate teams. This is a real reflection of what’s happening in West Papua, where there are two groups: those that would like to go through Special Autonomy, and others who would like to go straight to independence, both in peaceful ways.

Regarding Special Autonomy. It was started in 2001 by Megwati Sukarnoputri. But it failed, because it contained a clause that says a Papuan representative body, the MRP, had to be instituted first, but it wasn’t until after West Papua was divided into two provinces (in 2005). So the first failure was Megawati’s, because she divided West Papua into two—Papua and Irian Jaya Barat (which is now called Papua Barat). Then the Indonesian security sector suspected Special Autonomy was a golden way, a golden gate, to independence, because Special Autonomy was produced by Papuan academics and Papuan elders who walked around the territory for three months to get the peoples’ ideas. So they never implemented Special Autonomy.

Special Autonomy is meant to be for twenty years. Now it is 2016 and the dateline for evaluation is 2020. But the problem is it has failed. When SBY became president [in 2009], he knew that Special Autonomy had already failed, so he formed a Unit for Acceleration of Development in Papua and West Papua. But that also failed. So when Jokowi became president, he disbanded this program and is using his own approach, which is focused on infrastructure development, even though some Papuans do not like that kind of approach.

When SBY became president, he asked the Indonesian Research Institute (LIPI) to do a very comprehensive research, in an academic-not a political-way. Two of the lead scholars were Muridan from the University of Indonesia and Professor King from Sydney University. Both have since passed away, but they designed a road-map for West Papua based on the research. Muridan told The Jakarta Post that when he presented the research results, SBY’s inner circle didn’t accept them, saying that the research was too academic.

Q: I lived in West Papua for five years, and since 1983 I have been back another four times, and I haven’t met one West Papuan who wanted to stay with Indonesia. They all wanted independence. What we see on the ground is a lot of very active student groups, military in some of the jungles, the coast, the islands, the highlands, but we don’t see a lot of mass protest. We don’t see sit-ins, or strikes. There are lots of reasons for that, including fear of repercussions, because people do disappear, they get assassinated, and families are intimidated. Isaac, perhaps you could comment on that, in terms of where you think the majority of West Papuans are. The old people have suffered a long time and perhaps are really tired. Maybe they want independence, but they don’t have the energy to push it through or to sacrifice anymore. Or is it that they have given in, and are saying ‘Well if it happens it happens; we’ll leave it to Jacob and a few of you outside to make it happen’. Or is there a simmering resistance, like a lid on a boiling kettle, and it will just take something to take it off and the whole country will erupt.

ISAAC MORIN Thank you. In West Papua we have two beliefs, two faiths. Number 1, Jesus will come, and No 2, freedom will come. And West Papuans don’t know which one is coming first. More usefully perhaps we can reflect on Donald Trump and on Brexit. BREXIT exactly and the Donald Trump phenomena is what is happening in West Papua. But until now there is no survey, either from the government or from an NGO. I don’t know why. Maybe they are afraid to have the result, or maybe there’s no funding for doing the research. We don’t know. But if they did a survey, they will see that what happened with Donald Trump in USA will happen, and what happened in BREXIT in Europe will happen. Papuans are only waiting for the time. So I think the Indonesian government should do a kind of survey or research so that it has an idea about how to approach West Papua in this case. Because with no survey, I think there is a problem.

We see the phenomena in Jakarta. The governor of Jakarta is Catholic and Chinese, and he’s rejected by most Muslims in Jakarta, because in the Al Koran (Al Qaeda 51) it says that Muslims do not vote for Christians. What happens with elections now in West Papua is that one candidate (of a pair) is Papuan Christian, and the other candidate is migrant Muslim, because there are two populations in the cities. So if there is one Christian candidate and one Muslim candidate, the Muslim will get the vote of all the migrants plus the Muslims, and the Christian will get all the Christian votes but no Muslims. So, for example, if both in a pair of candidates are West Papuan, and another pair is one Papuan and one migrant, this latter one will be the winner. This was happening all over West Papua during the election. So it’s a hard problem to solve, and we don’t have a way, but there is always a way.

Q: Jacob, how important is the support of the Pacific nations for West Papua?

JACOB RUMBIAK Thank you for the question. I also congratulate the debate groups. The support of the Pacific countries, especially the Melanesian Spearhead Group, is very important firstly because West Papuans are Melanesian, we are not Asian. Recognition of West Papuans as Melanesians puts West Papua on the right track to explain to Indonesia and to the international community that we have a right to independence. The preamble of the Indonesian Constitution says that independence is the right of all nations around the world. So the recognition of West Papua by Melanesians is very important.

Secondly, we go to the Pacific because we want to go the right and noble way. West Papuans cannot negotiate with Jakarta, it is too difficult, we need a third party supported by the Pacific Coalition, especially the Melanesians. That will help West Papua and Indonesia. Our case must be taken back to the United Nations, which is the legitimate international body for solving national problems. Our case is a world problem, because Indonesia’s occupation was facilitated by the international community. That’s why we need a third party. That’s why we go to the Melanesian Spearhead Group. We didn’t want to create another problem between Indonesia and the Pacific. We just want a third party to bring West Papua case to the United Nations; to sit and talk about our future.

The future of West Papua can benefit Indonesia. We are not against Indonesia. The future of West Papua can also benefit the Pacific nations. So that’s our target in going to the Pacific, and of course our work will continue with the Africa Caribbean Pacific group and the United Nations.

[click for PDF of full transcript] debate-transcript-expert-panel

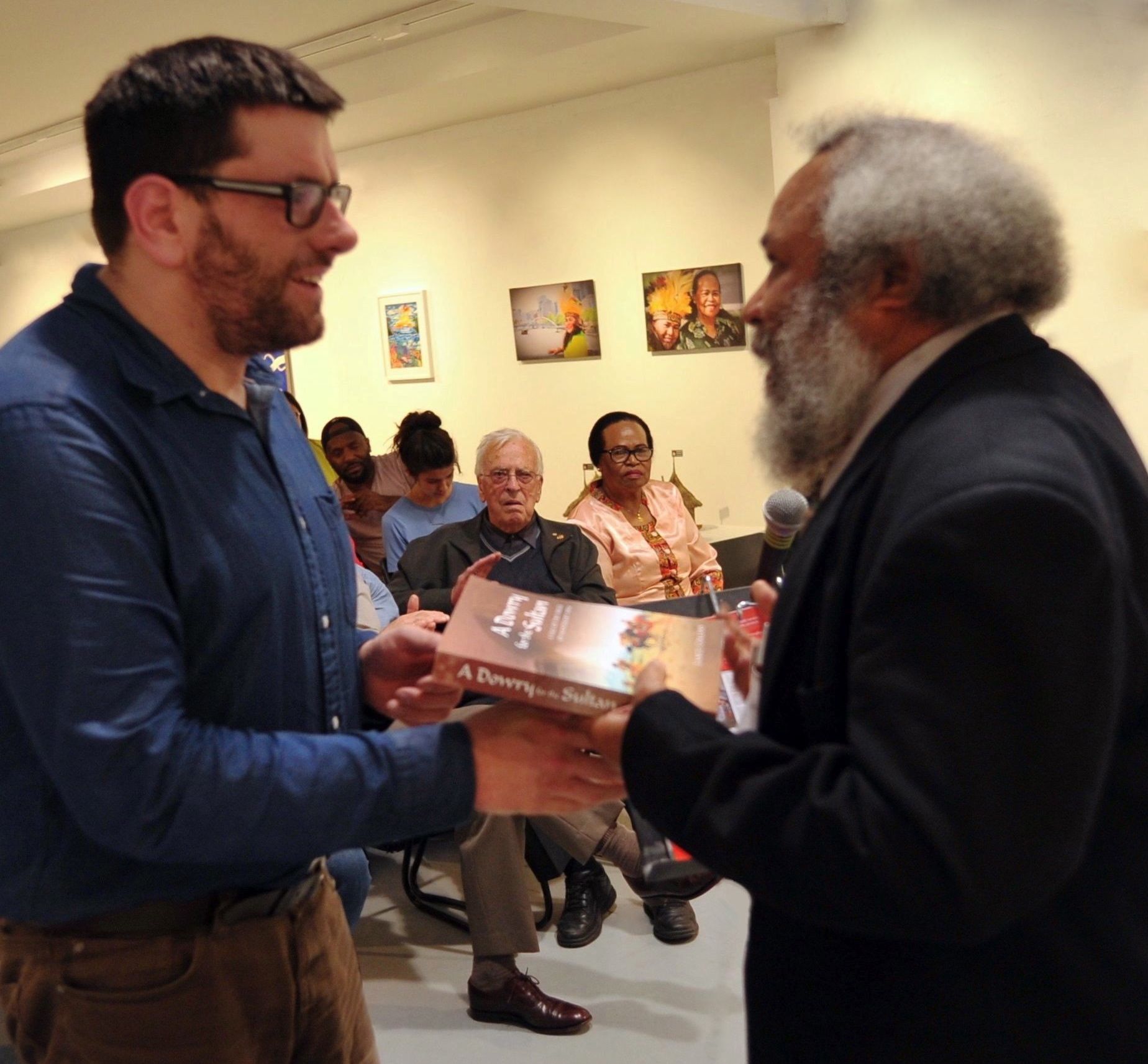

Jacob Rumbiak presenting a copy of Lance Collins’ A Dowry for the Sultan to Dr Jonathan Benney (Photo-Tommy Latueirissa-8 December 2016)

Debaters Kelvin Ka Wing Ng, Ben O’Shea, Rebecca De Kruijzer and Alessandra Chinsen with Louise Byrne from FRWP Womens Office in Docklands (Photo-Tommy Latupeirissa, 8 December 2016)

NOTES

1. [Click for] Debate details debate-details

2. Video Recording and Production: Fredrik Colvio Woirei and Mark Stevens. Live Streaming Jill Koppell (FRWP Womens Office in Docklands). With thanks to Annie McLaughlin from 3CR Radio for audio recording of Lunar Flares.

3. Dr Joe Toscano interviewing Ben O’Shea, 3CR Radio, 23 November 2016 (60′)

4. Bonded through tragedy; united in hope by Jim and Theresa D’Orsa documents and assays Bishop Hilton Deakin’s advocacy for East Timor’s self-determination from the time of the Santa Cruz Massacre in 1991 until the present day. Published by Garratt Publishing in January 2017 [Click for flyer] Hilton Deakin, A5 Flyer FINAL

5. Suggested Reading: The Murders of Gonzago by Errol Morris. Morris is the Executive Produce of the extraordinary documentary The Act of Killing directed by Josh Oppenheimer about the mass killings in Indonesia in 1965-66 [Click for PDF] The Murders of Gonzago