MONICA GUNAWAN (Papua New Guinea) DREAM HUNTER. “A brave and strong Melanesian woman, not afraid to lift a bow-and-arrow to hunt, standing up against her tribes traditions that do not allow women to hunt and fight.”

The 2016 Sampari Art Exhibition and sale for West Papua in the Australian Catholic University’s Art Gallery in Fitzroy in December 2016, hosted by the Federal Republic of West Papua’s office in Docklands, included a special Wall of Melanesian prints. The vibrant works sent by artists from Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Fiji, and Papua New Guinea projected kaleidoscopic views of Melanesian West Papua: as carriage of identifying tribal cultures, as agents of social change, as protector of complex ecologies, as children battered by war, as contested political identity at the centre of regional affairs.

All the prints were bought during the exhibition but are reproduced below, interspersed with excerpts from an essay by Sydney arts critic Ella Mudie:

The Sampari Art Exhibition for West Papua is an expression of the solidarity many Australians feel for the plight of our West Papuan neighbours. Further afield, an “agreement of feeling or action” that West Papua should be accorded the human right of self-determination unifies individuals across the Pacific. While this sense of regional solidarity is shared by every artist contributing work to the exhibition, it is especially prevalent in the Melanesian wall of art established to celebrate the unique political support of artists and cultural producers from Papua New Guinea, Fiji, Vanuatu, New Caledonia and Solomon Islands, for their Melanesian kin …

Whether artists can, or should wade into the arena of politics is a vexed question in the world of contemporary art. Within the framework of neoliberal capitalism, debate frequently involves heated discussion over the recuperation of critique and protest. In this environment of passionate disagreement over the role of the artist, the organisation of cultural events like Sampari along lines of solidarity, bringing together a diversity of artistic works in the name of a single cause – freedom for West Papua – provides an important outlet for expressing desire for change at a community level.

Works like Monica Gunawan’s vivid painting of a Melanesian woman rebuking tribal traditions by raising a hunting bow and arrow speak to the power of solidarity along gender lines. This is especially poignant in ‘Hope’ the portrait of a Papuan woman in Indigenous headdress by a West Papuan photographer. Solidarity with and between women acts as a subtle mode of resistance as it manifests not only in art but in everyday life, the realm wherein the personal becomes political and grassroots change often begins [Ella Mudie]

ANONYMOUS (West Papua) HOPE. “The Melanesian family has finally heard the West Papuan women’s cry, and they now have hope. Family is a gift from heaven, bound by the power of love. It is the strongest team, members have each others back. Its bonds can never be broken, even when obstacles try to tear it apart.”

The Melanesian states were colonies when the United Nations gifted West Papua to Indonesia in 1962, and may have been unaware of the theft of 416,000 sq kms of Melanesian land and the Indonesian border slip from Meridan 139E to Meridian 141E. A raft of name changes in West Papua helped mask the crime. Netherlands New Guinea became Irian Barat (then Irian Jaya), Hollandia became Jayapura (victorious city), Mount Carstenz overlooking what would be the (US) Freeport gold-and-copper mine became Puncak Jaya (victorious mountain), Dirk Hartog Island became Pulau Yos Sudarso after an Indonesian Navy commander. Little news escaped from the territory now categorised an Operational War Zone. Journalists and academics were denied visas. Subversion laws were exacted by a judiciary ruled by the military (which four years later slaughtered three million of its own citizens in Java and Bali). Only the ni-Vanuatu, urged on by their first prime minister Walter Lini, remembered the orphaned Papuans.

WOVEN BAGS, Tongoa-Shepherds Women’s Association in Vanuatu.

Craft work is often characterised as apolitical in the discourse of western art. However, the exchange of art and craft objects in Melanesia, like the woven bags exhibited by the Tongoa-Shepherds Women’s Association in Vanuatu, has long been implicated in complex political and social relations. For writers like the late Epeli Hau‘ofa, recognising such connections provides a politically transformative corrective to the notion that Pacific Island cultures are separated and isolated by the sea … when they are, in fact, an oceanic community based on voyaging.

West Papua’s assertion as a Melanesian state on 14 December 1988 was the initiative of Dr Thomas Wainggai, a senior public servant in Indonesia’s provincial administration with a law degree from Japan’s Okayama University and a PhD in Public Administration from Florida State University. Wainggai’s studies outside his homeland convinced him that West Papuans needed to resist the Indonesian occupation through dialogue-based negotiation generated by ‘justice, peace and love’ and to develop a national political structure based on their cultures, geographies and histories. He raised a flag in the name of West Melanesia on 14 December 1988 and was immediately arrested and incarcerated. Twelve months later eighty-eight academics from Cenderawasih University who had been developing and implementing the non-violent paradigm were also arrested and incarcerated. However the seeds of a resistance and nation-making endeavour that looked to the east more than the west had already been cast and taken root.

ALLAN MOGEREMA (Papua New Guinea) FREE PARADISE. “The beautiful bird-of-paradise is only found in West Papua and Papua New Guinea. For so long the Indonesians have held our bird-of-paradise in a cage built by humans.”

Melanesians feel something that anthropologists call ’embodied kinship’ when they hear about West Papua. Kinship recognition enacts long-established, reassuring, interconnecting patterns that are crucial to a human being’s sense of identity and security …. recalling a common history of origin and journeying across time and space, which in correlation with genetics, produces striking and inherently meaningful similarities. The Netherlands colonial administration was sensitive to this and provided for Papuan pastors to participate in Protestant church conferences in the Pacific and students to study at the Fiji campus of the University of South Pacific. After the establishment of the South Pacific Commission in 1947 (where the independence of the colonies was assumed even if discussion was curtailed to economic and social welfare) it sent Markus Kaisepo, a prominent bureaucrat from Biak-Numfoor, to the first meeting of the Commission’s indigenous leaders—an historic gathering in 1951 described by the Governor of Fiji (Sir Brian Freeston) as a Parliament of the South Pacific Peoples. The Unitary Republic of Indonesia severed these rich veins of continuity and solidarity on 1 May 1963.

West Papuans began lobbying the Melanesian Spearhead Group (MSG) in 2000 (Note 1). Papuans nation-making processes, as much as Indonesia’s bribes and blocking tactics, retarded their project to join the four-member inter-government group. However, during an intense week-long Reconciliation and Unity Summit for West Papuan Leaders in Vanuatu in 2014, a United Liberation Movement for West Papua (ULMWP) was elected from, and rendered accountable to, West Papua’s three key independence identities: Federal Republic of West Papua (Secretary-General Octo Mote and Executive Officer Jacob Rumbiak); West Papua National Parliament (Spokesman Benny Wenda); West Papua National Coalition for Liberation (Leonie Tanggahma, Rex Rumakiek). The historic summit was generated by church and women’s organisations across Melanesia; was sparked by the 2013 World Council of Churches Assembly in South Korea; was supported by West Papua’s Gereja Kristen Injili (GKI) Church; was sponsored by the Vanuatu Government and Pacific Conference of Churches; and was mediated by the Vanuatu Christian Council and Malvatumauri National Council of Chiefs. The following year, the MSG accepted the West Papuan movement as an ‘Observer’, although at the same time promoted Indonesia from ‘observer’ to ‘associate member’.

LAMBERT HO (Fiji) Drowning Sorrows

The term ‘solidarity’, deriving from nineteenth-century French, describes a “unity or agreement of feeling or action, especially among individuals with a common interest.” It is a notion that stirs, binds, and resonates most strongly during moments or events of crisis. The diverse nations and cultures of the Pacific have responded to Indonesia’s brutal occupation of West Papua with sympathy and solidarity as well as complicity.

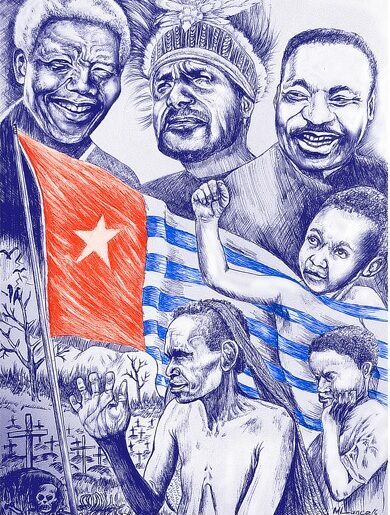

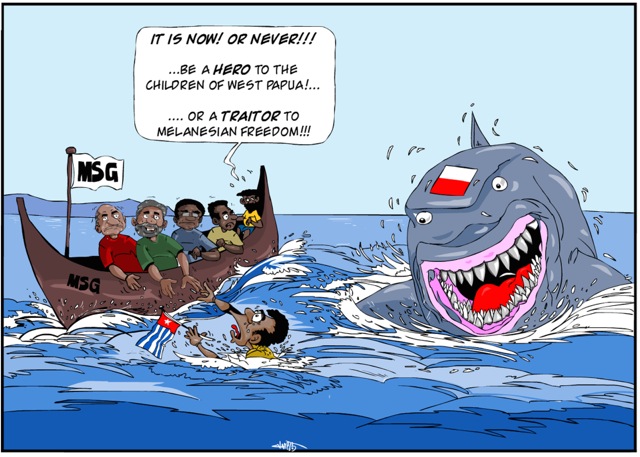

CAMPION OHASIO (Solomon Islands) Heroes or traitors for West Papua

The Island Sun newspaper, 24 June 2014

Humour and satire is another means through which solidarity is expressed as in Campion Ohasio’s cartoon ‘Heroes or Traitors of West Papua’. First published in the Solomon Islands newspaper The Island Sun in 2015 on the day the leaders of the Melanesian Spearhead Group met in Honiara to vote on West Papua’s membership, Ohasio’s drawing depicts a man flailing in the sea. With the West Papua morning star flag in one hand, he reaches out to the MSG leaders seated in a canoe to raise him from the clutches of the great white shark of Indonesia. This liberty to express a strong point of view through satirical humour without threat or fear of retribution, no matter how provocative the message, is one of the hallmarks of a free society and a point of solidarity that unites artists across cultures.

KINGSTON UYSSAI (Papua New Guinea) HELA WIGMAN WARRIOR “My work of a Hela Wigman warrior displays PNG’s rich timeless culture. Just across the border West Papuan cultures are having to fight for survival”

That West Papua’s resistance movement was recognised by the Melanesian Spearhead Group in 2015 can be attributed to a coalition of political, religious, academic and civic leaders from the Solomon Islands, a tiny archipelago of half-a-million Melanesians (Note 1). Prime Minister (and MSG Chair) Manessah Sogavare, assisted by Peter Forau (Director-General, MSG Secretariat 2011-2015) and Emele Duituturaga (Director, Pacific Islands Association of Non-Government Organizations), leap-frogged the MSG’s more compromised states (Papua New Guinea and Fiji) with the support of Polynesian and Micronesian leaders from the Pacific Islands Forum (Note 2). As the Pacific Coalition for West Papua based in Hawai’i University and advised by Solomon Island Professor Tarcicius Kabutaulaka, they were a strong voice in the 2016 United Nations General Assembly (Note 3).

PATRICK TONGA (Papua New Guinea) No hope and homeless

Today, Indonesia continues to solicit geopolitical support for its territorial claim to West Papua, asserting that the sovereignty of nations should be respected. The Australian government turns a blind eye to the Indonesian military’s violations of human rights in the name of ‘national interest’ and unwavering solidarity with its regional ally. Despite this, the solidarity with West Papuans that events like the Sampari Art Exhibition convey reveals citizens have a passionate desire for justice that seeks outlet in real and meaningful action.

MERE RASUE (Fiji) FOR MY FREEDOM “A photo of a child, face painted with the West Papuan flag, who is proud of his origin, lest we forget that the young ones also see the torture and the hardship … this child is seeking peace and a better future for his generation … we need to build a better life of freedom”

2016 Sampari Art Exhibition for West Papua

Sampari, Art and solidarity, Essay, Exhibition Catalogue

NOTES

1. The Melanesian Spearhead Group (MSG) was formed in July 1986 during a meeting of Heads of Government of Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, and the Kanak Socialist National Liberation Front (FLNKS), who agreed to work together in spearheading regional issues including the Kanak’s independence struggle in New Caledonia. On 14 March 1988, PNG Prime Minister Paias Wingti, Vanuatu Prime Minister Walter Lini, and Solomon Islands Foreign Affairs Minister Ezekiel Alebua signed the ‘Principles of Cooperation Among the Independent States in Melanesia’. FLNKS formally joined the MSG in 1989. Fiji joined in 1996. The MSG Secretariat in Port Vila, constructed by People’s Republic of China, opened on 30 May 2008.

2. The Pacific Islands Forum is a political grouping of fourteen Melanesian, Micronesian and Polynesian independent and self-governing states, as well as Australia and New Zealand (that is, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea, Fiji; Federated States of Micronesia, Republic of Marshall Islands, Kiribati, Palau, Nauru; Cook Islands, Tonga, Tuvalu, Niue, Samoa). In 2015 the Forum noted West Papua’s application for membership subject to a PIF Fact-finding Mission to West Papua, which Indonesia subsequently rejected.

3. Speakers to the 2016 UNGA were Prime Minister Sogavare (Solomon Islands), Prime Minister Salawi (Vanuatu), Prime Minister Pohiva (Tonga), President Hilda Heine (Federated States of Micronesia), Prime Minister Sopoaga (Tuvalu), President Divavesi Waqa (Nauru), Dr Caleb Otto (UN Representative, Republic of Palau).