Introduction

This paper traces the establishment of the Federal Republic of West Papua (FRWP) during the 3rd Papua Congress on 19 October 2011. ((The paper draws on Don Flassey’s Basic Guidelines, Federal Republic of West Papua State Secretariat, West Papua, May 2012; Louise Byrne’s Melanesian West Papua over-riding Indonesian colonialism 1998—2012 in ‘Continuity and contradictions in West Papua’s transition to independence’ Globalism Institute, Melbourne; and my paper West Papuan independence policies(‘Comprehending West Papua’, Peter King, J Elmslie and C Webb-Gannon (eds) Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies, University of Sydney, 2011). It also draws on Solving the political impasse between Indonesia and West Papua—the readiness of West Papuans to run their own country(Jacob Rumbiak, International Peace Research Association, Sydney University, July 2010), which I also presented in 2010 to the ‘Washington Solution’ seminar at George Mason University (US), Cordillera Peoples’ Alliance Conference (Philippines), the Kanaky Labour Party Conference in New Caledonia and Parti Travailliste Congress on Iaai Island.)) It identifies the institutions involved, and outlines the FRWP’s political priorities and social objectives. It assumes that Indonesia will adopt self-determination principles (as defined in the New York Agreement 1962), and navigate an early removal of its political and security infrastructure. It implies that states, and nations, and sub-state identities like universities and trade unions, will recognize they have more to gain than lose from entering into direct relationship with the FRWP.

Forming an independent state within Indonesia’s so called reformasi (since 1998) has been complicated as much by the government’s manipulation and abuse of its own special autonomy laws and regulations as by its opposition to independence. A turning point, in June 2010, was the MRP’s ‘return’ (rejection) of special autonomy. The MRP/Papuan People’s Assembly—a creation of special autonomy—is a tri-partite assembly of tribal, female, and religious leaders elected by the people but from a group of nominees selected by the government. (It is therefore different to the Dewan Adat Papua/Papua Traditional Council formed in 2002 by the leaders of the nation’s seven tribal states). The MRP’s boldness in jettisoning its political and financial sponsor shook Jakarta. President Yudhoyono ordered “an audit to examine which of our policies have been incorrectly focused? …. is it the management, the budgeting, or the overall efficiency?”. ((Papua provinces development funds: SBY The Jakarta Post, 30 July 2010.)) His spokesperson later admitted “the government managed to deliver a good public show .…. but we have achieved almost nothing of substance, to be honest”. ((Little achieved in politics this year The Jakarta Post, 20 December 2010.)) Almost on cue, the Harvard Kennedy School Indonesia Program published its dismal report on institutional transformation since the discharge of Suharto. ((Democracy has not eliminated corruption or strengthened the rule of law…the economic oligarchy has survived the crisis and its relationship to the state is largely unchanged…[there is still] widespread institutional corruption particularly of the judicial system and the police force…weak legal and regulatory infrastructure, patrimonial politics, disempowered citizens, political gangsterism …child and maternal mortality three times that of Vietnam, 20% of children underweight ….” (from From Reformasi to Institutional Transformation: a strategic assessment of Indonesia’s prospects for Growth, Equity, and Democratic Governance Harvard Kennedy School Indonesia Program, 2010). )) Meantime, Papuans activists had organised the (first) US Congressional Hearing on West Papua, ((Preliminary Transcript of September 22, 2010 Congressional Hearing on West Papua Federal News Service, 22 September 2010 (http://www.etan.org/news/2010/09wpapuahearing.htm).)) and the West Papua National Authority had installed two training officers at George Mason University. ((Herman Wainggai, nephew of Thomas Wainggai (West Melanesia 1987—) was a political prisoner 2001, 2002—2004, and in 2005 led 43 Papuans to Australia in a traditional canoe (http://hermanwainggai.blogspot.com.au/). Frans Kapissa was the sociology lecturer at Cenderawasih University and intellectual and emotional mentor for the non-violent student movement during the 1990s. He was heavily bashed by the military during demonstration on campus in 2006 (The Age, 27 March 2006 Cover-up fear over dead in mine riot: pictures of the bloody confrontation that rocked West Papua).))

The Indonesian Republic, now in its sixtieth year, presents little incentive for West Papuans to reconsider their long-standing ambition. The 2012 UN Human Rights Council’s Universal Periodic Review produced an embarrassing array of recommendations—including many not addressed from the 2008 UPR, and many contradicting the government’s own eulogistic report. (( Human Rights Council, Universal Periodic Review 2012 Indonesia, OHCHR Summary (www.upr-info.org/Review-2012,1478.html); National Report (www.upr-info.org/Review-2012,1478.html). ))FRWP Prime Minister Waromi described it—from his prison cell—as ‘proof, beyond reasonable doubt, that Indonesia has no place in Papua”. ((Press Statement, Secretariat for the Prime Minister, Federal Republic of West Papua, 15 June 2012. )) ((Referendum not up for discussion: SBY The Jakarta Post 30 Jun 2012 (www.thejakartapost.com/news/2012/06/30/referendum-not-discussion-sby.html). ))

The 2009 UN Development Program’s Ten-year review of decentralization reported lack of legal clarity between central, province, and district governments had retarded planning as well as implementation, budgeting, and monitoring processes. ((Ten Years implementing Indonesia’s Decentralization: reformulating the role of the province UN Development Program 2009 (http://www.undp.or.id/press/view.asp?FileID=20090625-1&lang=en).)) The Indonesian Interior Ministry’s own report on decentralization (June 2012) cited a failure-rate of 78%, Minister Fauzi (a former New Order officer) threatening his colleagues with ‘coupling back to the parent’. ((www.depdagri.go.id/news/2012/06/18/otonomi-daerah-78-daerah-pemekaran-gagal. Those at the meeting threatened by Fauzi included State Secretary Silalahi; as well as the ministers for Politics & Security (Djoko Suyanto) Maritime Affairs (Fadel Muhammad) Energy & Minerals (Darwin Saleh) Transport (Freddy Numberi) Trade (Mari Pangestu) Forestry (Zulkifli Hasan) Culture & Tourism (Jero Wacik) Cabinet Secretary (Dipo Alam) Deputy Foreign Minister (Triyono Wibowo) Gamawan Fauzi (Home Affairs). See Michael Buehler’s Angels and Demons (Inside Indonesia, 22 Apr 2012; www.insideindonesia.org/stories/angels-and-demons-22042912) for Fauzi’s seemless transformation from New Order officer, to reformist governor, to advocate of centralism. )) More specifically, the Sultan of Jogjakarta, as keynote speaker at a University of Indonesia seminar in May 2013, asserted “Special Autonomy has failed the people of Papua …the state is present in the form of military forces ….. human rights and state violence occur…the conflicts are not horizontal but vertical between the government and the people….. Indonesia has failed to Indonesianize Papua”. ((Sultan Hemengku Buwono X Fifty years of Papua in Indonesia, University of Indonesia, 14 May 2013 (http://suarapapua.com/2013/05/paradoks-separatisme-dan-kemiskinan-penduduk-asli-papua-selama-50-tahun-dalam-indonesia/))) The Sultan’s critique is the most reality-based analysis since the warning in 2008 by General Ryacudu (Chief of Staff, Indonesian Army 2002—2005) that “West Papua satisfies all pre-requisite criteria matters pertaining to the governance of an independent nation state”. ((Tempo Interaktif, 27 August 2008. Ryamizard Ryacudu was speaking at Gajah Madah University’s 63rd anniversary celebrations of the Indonesian Republic.))

Since its formation in 2011, West Papua’s peak political management has continued the assemblage of state and governance advanced by the West Papua National Authority since 2004. (The WPNA is rooted in the practice of ‘learning democracy by doing it’). ((The concept of ‘becoming a democracy through practice’ is advocated by UN executives like Roland Rich, (Roland Rich, UN Democracy Fund, New York, 17 September 2012, at http://webtv.un.org/search/panel-discussion-on-the-occasion-of-the-international-day-of-democracy:-democracy-education/1846011345001?term=democracy%20education with specific reference to West Papua at 1:11:30—1:17:00). )) Unfortunately, few foreign analysts have expressed any interest in our carefully crafted nation-building (as distinct from resistance). ((Danilyn Rutherford claims “Outsiders have tended to view the West Papuans as far too primitive to act as the mature, rights-bearing subjects of popular sovereignty that liberal thinkers place at the heart of the modern nation form” (Rutherford, D Why Papua wants freedom: the third person in contemporary nationalism Public Culture Vol. 20 No. 2, 2008:345-373, Duke University Press). )) This paper details the Federal Republic of West Papua’s institutional development and policies, and includes a model of financial re-distribution. This model demonstrates how the extraction of just two metals by an (extant) mining company generates taxes and royalties of three billion dollars annually. This gold has been ear-marked for the reconstitution of Melanesian identity and lifestyle. The figure itself represents $1,775 per capita per annum ($4.86 per man, woman and Papuan child per day).

Declaring the Federal Republic of West Papua at the 3rd Papuan Congress

The Federal Republic of West Papuan was established during the 3rd Papuan National Congress that took place on Zaccheus (soccer) Field in Abepura between 16 and 19 October 2011). ((The 3rd Congress was forced to relocate to the Taboria soccer field after the director of Cenderawasih University yielded to government pressure to have it moved outside the grounds of the university. For West Papuans, the Taboria soccer oval is Zakheus Tunas Harapan Padang (zakheus/pure and righteous; tunas/bud; harapan/hope; padang/field). )) The new state is the broadest representation possible of mainstream Papuan ambition—and therefore a statement about Papuan nationalism, as well as a political-management construct for the delivery of independence—and thus a statement about resistance to Indonesian colonialism.

The 3rd Congress was a four-day assembly of mainstream Papuan society, namely five-thousand intellectuals, church leaders, and senior tribal leaders (with thousands more observing). ((According to Fery Marisan (director of ELSHAM, West Papua’s human rights NGO) “The radical fringe stayed away from the congress because they think it’s not radical enough” (Six dead, many injured and in hiding New Matilda, 20 October 2011). By radical fringe, he meant the TPN and KNPB, which have both since recognized the FRWP.)) It opened with a day of prayer. The three-day discussion opened with a tifa-drum ceremony, symbolically heralding the people’s ambitions and determinations; with leaders responding understood to be heavily obliged to shoulder them. The respondents were Edison Waromi from the West Papua National Authority, Forkorus Yaboisembut from the Dewan Adat Papua/Papua Tribal Council, Elizier Awom for TAPOL, and Septinus Paike for the West Papuan National Coalition for Liberation. ((West Papua National Coalition for Liberation (WPNCL) presented at the Opening Ceremony of the 3rd Congress, but did not join the Federal Republic of West Papua. The WPNCL is an OPM-exile dominated group set up in Vanuatu in 2008 ‘to bring all resistance movements into one body’, after a meeting in Malaysia in 2007 organized by Deakin University academic Damien Kingsbury and funded by Olof Palme Peace Foundation (John Ondawame 2011:pp238, 242 Papuan perspectives on peace in West Papua in ‘Comprehending West Papua’, Sydney University). )) Federalism was adopted as the most appropriate political architecture for Papua’s multi-tribal, multi-religious, multi-ethnic population. ((‘Federalism’ has been taboo in Indonesia since 1950, after Sukarno destroyed the Federal Consultative Assembly that represented much of the non-Javanese population during the war with The Netherlands (1945-49) and the consequent sovereignty-transfer agreement.)) Edison Waromi, President of the West Papua National Authority, which originated in Thomas Wainggai’s West Melanesia movement (1987—), was elected prime minister. ((rime Minister Edison Waromi, a lawyer and theologian, has been a political prisoner for much of his adult life: for ten years 1989—1999; in 2001; in 2002 as President of the United West Papua National Front for Independence; in 2003—2004 as President of the West Papua National Authority. He is currently in prison again (2012—2015) as President of the Federal Republic of West Papua.)) Forkorus Yaboisembut, Chair of the Dewan Adat Papua established at the conclusion of The Presidium’s Indigenous Seminar in 2002, was elected president.

The Indonesian government responded predictably to the establishment of an independent Melanesian state. ((West Papua has been described as ‘the most militarized area in the world, with one security identity per 100 citizens, compared to Iraq’s ratio in 2009 of 1:140’ (Philip Jacobsen Obamacopters Give West Papuans Another Reason to Worry, 29 Aug 2012, Truthout—at http://truth-out.org/news/item/11169-obamacopters-give-west-papuans-another-reason-to-worry). Jacobsen is quoting Indonesia by James Page, Syafuan Rozi Soebhan and Jeremy Peterman in ‘State violence and the right to peace’ (ed) Kathleen Malley-Morrison, Greenwood Publishing Group United States 2009.)) Six weeks before, in August 2011, it had implemented its ‘Military Enters Village’ (TMMD) program—according to Army Chief-of-Staff General Edi Wibowo “in villages that we believe are likely to be influenced by the OPM”. ((Military Vows Retaliatory Action in Papua The Jakarta Globe, 4 August 2011; West Papuan leader questions Australia’s gift of Hercules aircraft to Indonesian republic AWPA-Melbourne Press Release, 5 July 2012, at http://hermanwainggai.blogspot.com.au. TMMD (TNI Manunggal Membangun Desa/Indonesian National Armed Forces United to Develop Villages) is a revamp of the New Order’s dwi fungsi/dual function, where military and police work alongside society constructing ‘physical infrastructure like roads and worship centres’ and ‘non-physical infrastructure like nationalism, territorial building, defense in order to strengthen unity between TNI and the people for the benefit of the Republic of Indonesia’ (Berita, Jakarta, 10 Oct 2011, www.beritajakarta.com/english/PrintVersion.asp?ID=20634). General Wibowo is President Yudhoyono’s wife’s brother, the son of Brig-General Sarwo Edhie, the KOPASSUS commander known throughout Indonesia as ‘the bloodhound of Java’ (for massacres in Java, Bali, and Sumatra in 1965-66), and the Military Commander in West Papua before during and after the Act of Free Choice in 1969.)) Soon after President Yaboisembut read the declaration, armoured vehicles, which had surrounded the open-air congress for three days, swarmed through the gates of the soccer field. Soldiers and police opened fire. Snipers in trees found targets. Hundreds of Papuans, including the FRWP executive, were kicked and beaten with batons, bamboo sticks, rifle butts; then tortured into leaping, like frogs, across the field. ((Indonesian security response to FRWP: Aljazeera, 22 Oct 201 Indonesian forces raid Papuan independence gathering (http://english.aljazeera.net/video/); The Sunday Age, 23 Oct 2011 Indonesia, Papua and the prisoners of history; ABC-Lateline, 27 Oct 2011 West Papuans attacked by Indonesian Army; West Papua Media Police and army open fire on Papuan Congress (westpapuamedia.info/2011/10/19/police-and-army-open-fire-on-papuan-congress); New Matilda 20 Oct 2011 Six dead, many injured and hiding (http://newmatilda.com/2011/10/20/troops-open-fire-papuan-gathering))) Four students and two PETAPA (Guardians of the Land of Papua) were assassinated. ((James Gobay (age, 25), Yosaphat Yogi (28), Maxsasa Yewi (35), Daniel Kadepa (25), and the PETAPA’s Yacob Samonsabra (53), Pilatus Wetipo (40). PETAPA (Guardians of the Land of Papua) is an unarmed peacekeeping force, specifically trained in non-violence, set up by Dewan Adat Papua in July 2011 after a series of violent incidents by Indonesian security forces and transmigrasi militia.)) Three hundred were arrested. Doctors later confirmed twelve fractured skulls. President Yaboisembut, Prime Minister Waromi, and two congress organizers were charged with subversion under Article 106 of the Criminal Code; a third organizer under the 1951 Emergency Law. ((Besides Yaboisembut and Waromi, the ‘Jayapura Five’ included Selphius Bobii, August Sananay Kraar, and Dominikus Sorabut (http://westpapuamedia.info/tag/human-rights/page/6/). (Papuan) Chief Justice Jack Oktovianus of the Jayapura District Court found: “The defendants jointly tried to commit treason with the intention of allowing the country or part of the country to fall into the hands of the enemy” (Jakarta Globe Indonesian Court Indicts Papuan Activists for Treason 30 January 2012). The other judges were I Ketut Nyoman Swarta, George Mambrasar, Orpa Martina, Willem Marco.)) (These ‘Jayapura Five’ were well defended by a team of young West Papuan lawyers led by Olga Hamadi and Gustav Kawer, but ultimately incarcerated for three years; 30 January 2012—2015).

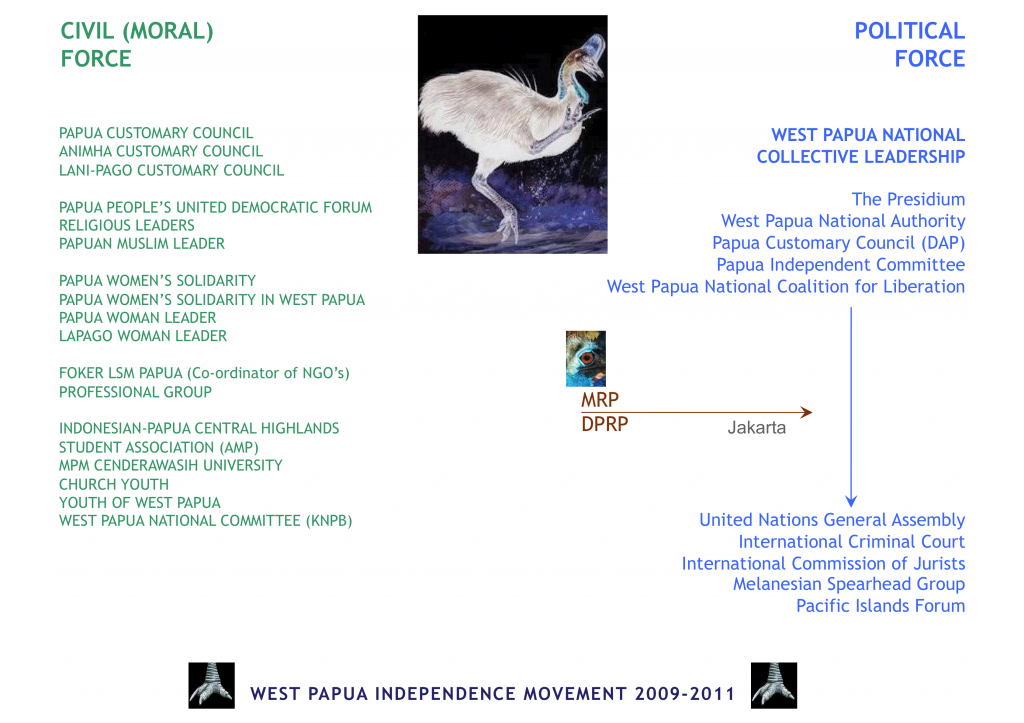

The 3rd Papua Congress was organized by the West Papua National Collective Leadership, after a reconciliation agreement—PAPUA NATIONAL CONSENSUS—between the PRESIDIUM and WEST PAPUA NATIONAL AUTHORITY in May 2009. ((Papua National Consensus, 14 May 2009 (see http://etan.org/issues/wpapua/0905papconsensus.htm))) (The West Papua National Coalition for Liberation joined the Consensus eighteen months later, but subject to the name being changed to ‘West Papua National Collective Leadership’). Forty leaders had participated in meetings (22 April to 14 May 2009) designed by the Papuan student movement as a space for leaders of autonomy-based development to meet independence leaders and ‘reunite all the political components of the struggle under a common direction’ . The agenda, ‘building Papuan self-determination’ (specifically as ‘not part of Indonesia’), was mediated by TAPOL—an informal collective of former political prisoners—and discussed in front of Papuan academics, religious leaders, and politicians. A key participant was the Papua Council—whose Presidium (executive) was still influential through the work of individuals like Secretary-General Thaha Alhamid, and the loyalty of organizations it had spawned—namely Dewan Adat Papua (2002—) and West Papuan Solidarity of Women (2001—). ((PAPUA CONSENSUS DECLARATION (2009): respect for indigenous Melanesian people as owners of the land, cessation of transmigration and funding for Special Autonomy, opening West Papua to international community, revision of Act of Free Choice, and a UN referendum; signed by Tom Beanal, Thaha Alhamid, Pdt Herman Awom (Presidium Vice-Chair, Secretary-General, Moderator); Edison Waromi & Terianus Joku (West Papua National Authority President & President-of-Congress); and Eliaser Awom (TAPOL).)) The Consensus viewed nation-making in terms of ‘learning democracy by doing it’, long advocated by UN executive Roland Rich, but also the West Papua National Authority since 2004. ((See Jacob Rumbiak 2011:253. Also Roland Rich, UN Democracy Fund, New York, 17 September 2012 (http://webtv.un.org/search/panel-discussion-on-the-occasion-of-the-international-day-of-democracy:-democracy-education/1846011345001?term=democracy%20education). )) The Presidium was thus assigned responsibility for developing a parliament, and Dewan Adat Papua for a judiciary.

Key institutions of the Federal Republic of West Papua

The FRWP’s key identities, elected at the congress, are Prime Minister Edison Waromi and President Forkorus Yaboisembut. Waromi is president of the West Papua National Authority, an organization of academics, students and political prisoners, with roots in ‘West Melanesia’ (1987—), and working as a transitional government since 2004. Yaboisembut is head of the Dewan Adat Papua (Papua Tribal Council), the peak representation of West Papua’s seven tribal states (and three-hundred adat leaders), formed at the conclusion of The Presidium’s ‘Indigenous rights’ seminar in 2002. The alignment of these two influential institutions means that Papuan resistance and nation-making is led by a coalition of intellectuals politicized and empowered by years of incarceration and tribal leaders with knowledge and authority throughout the sub-nation localities.

West Papua National Authority

The origins of the West Papua National Authority are in Thomas Wainggai’s dialogue-driven West Melanesia movement of 1987. ((Thomas Wainggai raised the flag of ‘Republic of West Melanesia’ on 14 December 1987, was immediately incarcerated, and poisoned in Cipinang Prison in 1996. Wainggai was an experienced civil servant who had worked for both the Dutch and Indonesian administrations in West Papua between 1959 and 1986. During that time he graduated from Okayama State University in Japan in 1969 with a degree in Law, from New York State University in 1981 with a Masters degree in Public Administration, and from Florida State University in 1985 with a PhD in Public Administration (Decentralization of national development in developing nation states: a comparative analysis).)) Thirty UNCEN academics who followed his logic, of re-claiming Melanesian land stolen in 1962, were incarcerated in Java in 1988, leaving one young lecturer to teach students how to instill the struggle with legal argument and political debate across better-recognized understandings of ‘justice, peace and love’. Most of the acadmics were released after Suharto’s discharge, by which time the students had introduced the cultural-political paradigm to Papua New Guinea and Vanuatu. In truth the construct was more readily recognized in these Melanesian kin states than in West Papua, where resistance—since the debilitating split of the OPM in 1977—had tended to ignore the complementary task of nation-making.

In the chaos of the post-suharto space, West Melanesia advocates concerned themselves with developing a pyramid management structure for Papua’s extensive grass-roots resistance and nation-making aspirations. In February 2002 they hosted a meeting of the OPM, Presidium, and West Papua New Guinea National Congress, on Sir Tony Bais’ tribal land in Wewak (PNG). In the wake of the Presidium’s demise, reconciliation was essential, but so too West Melanesia’s idea of ‘practicing democracy’, and the ‘United West Papua National Front for Independence’ was established to begin a ‘democracy by doing’ project. Boundaries were drawn between political development, human rights, and traditional customary issues; the churches and NGOs delegated resposibility for human rights, and the newly formed Dewan Adat Papua/Papua Tribal Council for distinctly indigenous issues. At the next meeting, in 2004, again in Wewak, the process was furthered, and an executive, legislative, and judiciary elected. At this meeting the name ‘West Papua National Council’ was adopted, but later ratified, in August 2004, as the ‘West Papua National Authority’. ((The name ‘United West Papua National Front for Independence’ was changed to ‘West Papua National Council’ on the advice of international activists who believed ‘front’, post-911, would attract ‘terrorist’ classification. At a supplementary meeting, in August 2004, the name-change was ratified as ‘West Papua National Authority’))

The West Papua National Authority sought to set up a transitional government through which reconciliation between Papuan leaders could be pursued, as well as relations with Jakarta and the international community . In terms of international relations, it co-operated with an international campaign for a review of the New York Agreement (1962) but was equally concerned with establishing formal relations with its Melanesian kin states. It turned first to Vanuatu, and after years of negotiation, signed the ‘Unity Day Port Vila Vanuatu Declaration’ with the Maraki Vanuariki Council of Chiefs, Port Vila Council of Chiefs during a summit in Port Vila (16 November—1 December 2007). In the Melanesian face-to-face way of formal agreements, The Authority’s Jacob Rumbiak, the only executive in exile, was appointed a paramount chief. In such manner Vanuatu’s powerful chiefs loaded their government with responsibility for listing West Papua with the Melanesian Spearhead Group, Pacific Island Forum and Africa Caribbean Group; for sponsoring West Papua back onto the UN Decolonization List; and for facilitating a UN self-determination referendum.

The task facing the West Papua National Authority in setting up a transitional government within Special Autonomy conditions was monumental (and further exacerbated by the division of West Papua into two provinces). Activists and politicians had to confront the flood of Islamic-caliphate money that was funding militia and the military, building mosques, sponsoring agricultural plots for Muslim migrants, and removing Papuan children for a pesantren education in Jakarta. At the same time, Special Autonomy’s ‘western money’ was (and still is) being used to buy Papuan political support in the form of badly conceived and barely managed ‘development’ projects (that are mostly about buying tribal land and water for logging and mining). There was some relief in 2005 when the Dewan Adat Papua formally denounced Special Autonomy, and more in 2009 when forty leaders sat together to ‘build Papuan self-determination’ specifically as ‘not part of Indonesia’. The Authority was then charged with responsibility for delivering political independence, and within two years had garnered broad (Papuan) support for a federal construct, which it believes is the most appropriate for the nation’s multi-tribal, multi-religious, and multi-ethnic population. ((Since the Indonesian occupation, West Papuans have been reduced from a majority population (99% in 1962) to a distinct alarming minority (48.73%) with an annual growth rate in 2010 of 1.84% compared to the non-Papuan rate of 10.82% (Jim Elmslie, West Papuan demographic transition and the 2010 Indonesian census: “slow motion genocide” or not? CPACS Working Papua No.11/1, Sept 2010, Sydney University). ))

Dewan Adat Papua/Papua Tribal Council

The Dewan Adat Papua is a peak representation of West Papua’s seven tribal states. ((Adat is a complex of tribal rights and obligations that ties together history, land, and law (see, for example, Jamie Davidson & David Henley, 2007:p3 The revival of tradition in Indonesian politics:the deployment of adat from colonialism to indigenism Routledge, New York. )) (The seven tribal states are historic institutions, represented on the Morning Star flag by the seven blue horizontal bands). ((Adat is a complex of tribal rights and obligations that ties together history, land, and law (see, for example, Jamie Davidson & David Henley, 2007:p3 The revival of tradition in Indonesian politics:the deployment of adat from colonialism to indigenism Routledge, New York. )) The Dewan Adat was formed at the conclusion of the Presidium’s ‘Indigenous rights’ seminar in Jayapura on 26 February 2002. It self-identifies as steward of the land and natural world, as underpinning the self-determination processes, and as guardian of the social and moral order (see DAP Foundational Statement). ((AP’s Foundational Statement was signed by Max Werimon—Chairperson, Willem Bonay—Secretary, Ham Nawipa, Yakomina Isir, and Marthen Mambrasar (see International Alliance of Indigenous and Tribal Peoples of the Tropical Forests, Nairobi, 18 November 2002, at http://www.international-alliance.org/Int_Conference_4.html). DAP’s foundational statement referenced the Universal Declaration on Human Rights; UN draft of The rights of Indigenous Peoples; ILO Convention 169 on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Rights; 2nd Papua Congress resolutions; Letter of Papua Traditional Council No. 021/SK LMA/Papua/A/IX-2001 regarding Great Council of Papua Traditional Communities; Letter of permission from Papua Police No. POL.:/SI/05/II/INTEl.2 (2 February 2002).)) DAP’s annual meetings, each in a different state, have always attracted at least three hundred of the nation’s adat leaders. ((Broek, Evelien van den (Dewan Adat Papua, an upcoming power Europe Pacific Solidarity Bulletin Vol. 13, No. 3, July 2005). DAP’s 2003 meeting was in Sentani, 2004 in Biak, 2005—Manokwari, 2006—Fak Fak, 2007—Merauke, 2008—Wamena (John Wing, Peter King Genocide in West Papua? The role of the Indonesian state apparatus and a current needs assessment of the Papuan people Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies, Sydney University 2005; http://sydney.edu.au/arts/peace_conflict/docs/WestPapuaGenocideRpt05.pdf.)) Its formation was inspired by the UN Declaration on the rights of indigenous people—which Viktor Kaisiepo, the Presidium’s Netherlands-based representative for international affairs, worked on for years. ((Pieter Drooglever 2011:26 (The pro- and anti-plebiscite campaigns in West Papua: before and after 1969, in ‘Comprehending West Papua’ Peter King, Jim Elmslie & Camellia Webb-Gannon, Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies, Sydney University). Viktor Kaisiepo is the son of Markus Kaisiepo, a leading nationalist during the Dutch period and member of the 1961 New Guinea Council. Viktor returned from Holland for the first time to participate in The Presidium’s Congress in May 2000. ))

The important features of the DAP foundational statement are:

- Land, waters, air and all the natural resources are the property of the indigenous owners and cannot be purchased by any other parties

- Development actors including NGO’s and the private sector to respect the rights of traditional landowners, their activities subject to the consent of the tribal councils

- All tribes within the indigenous Papuan communities are to abide, respect and promote the fundamental rights—both individual and collective—of indigenous Papuans

- Traditional Papua communities are obliged to utilize their natural resources to support the political aspirations and economic perspectives of the indigenous peoples

- The indigenous peoples to engage and cooperate with any third party in order to transform and free Papuan from violence, harassment and oppression

- Traditional Papua communities must respect and value non-Papua communities in Papua and not entertain discriminate on the basis of tribe, religion and race

Some have claimed the Dewan Adat Papua inherited the Presidium’s reputation of opposing the government’s handling of Special Autonomy while not necessarily opposing autonomy itself. (The DAP inadvertently fuels such claims with its well-appointed government office—albeit in a state that doesn’t recognize ‘indigenous’ people!). ((ndonesia adopted the UN’s Declaration on the rights of indigenous people in 2007, but then refused to ratify it, Foreign Minister Marty Natalagawa claiming the republic recognizes that other states have indigenous people, but that Indonesia doesn’t! (See Indonesia treats its indigenous peoples “worse than any other country in the world” 3 October 2012, at http://www.redd-monitor.org/2012/10/03/indonesia-treats-its-indigenous-peoples-worse-than-any-other-country-in-the-world-survival-international/). The Republic’s formal response to the UN Human Rights Council’s Universal Periodic Review of Indonesia in 2012 was “Indonesia does not recognize the application of the indigenous people concept as defined in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples” (UN Human Rights Council, 21st Session, 5 September 2012, Agenda Item 6, Universal Periodic Review).)) However, as tribal leaders of prescribed territories, each DAP member is searingly close to the grassroots that has always driven the independence movement. It was this sort of pressure that forced DAP to legislate, in February 2005, for direct action against the government for its failure to implement Special Autonomy. Newly elected chair Forkorus Yaboisembut penned an ultimatum for the government to deliver by 15 August 2005 (the 43rd anniversary of the New York Agreement). The government’s first response (in April 2005) was to dispatch extra military specifically tasked to run intelligence operations, through local militia, against DAP identities. The DAP then published a list of specific complaints, including the (illegal) erection of a second province, failure to install the Papua People’s Assembly/MRP), inadequate representation of the tribes, human rights abuses, appalling living conditions. President Yudhoyono replied with a presidential decree ordering the erection of a BAKIN-Intelligence office in Biak Island specifically tasked to ‘dissuade’ the population, starting with the governor, from supporting the DAP protest. ((Intelligence agents disguised themselves as street-level fish traders and security guards in government and private offices (www.infopapua.org/artman/exec/view.cgi?archive=36&num=140&printer=1). )) Huge rallies proceeded anyway, on 12 August 2005, in Jayapura, Manokwari, Sorong, and Biak. ((There were 15,000—20,000 in the DAP’s main march from Abepura to Jayapura (17 kms), 2,000 each in Manokwari and Sorong, and 1,000 in Biak (Tribal Council rejects special autonomy law WPNews, 19 October 2005, at www.infopapua.org/artman/exec/view.cgi?archive=36&num=140&printer=1).)) The government then implemented its Special Autonomy commitment for a MAJELIS RAKYAT PAPUA (MRP/Papua People’s Assembly), but with forty-two tribal, religious, and female Papuans selected by the government. ((Growing Papuan protest over central government creation of “Papua People’s council” with minimal Papuan input The Jakarta Post, 27 October 2005, in ‘The West Papua Report September 2005’ Robert F. Kennedy Memorial (see http://wpik.org/Src/WPReport_Oct_05.pdf).))

The MAJELIS RAKYAT PAPUA (MRP) requires explanation because it is an exclusively indigenous house of the Papuan provincial parliament comprised of equal numbers of tribal, religious, and female representatives. It was, in the beginning, a central feature of the (Papuan) autonomy bill passed by the province-level parliament in Jayapura early in 2001.13 However, that bill was heavily modified in the Special Autonomy Law signed by President Sukarnoputri in 2001. ((For the differences between the Papuan Autonomy Bill and the Special Autonomy Law (2001) see Rodd McGibbon 2004:73 (Secessionist Challenges in Aceh and Papua: Is Special Autonomy the solution? East West Centre, Washington 2004; at www.eastwestcenter.org/publications/secessionist-challenges-aceh-and-papua-special-autonomy-solution).)) The Papuan autonomy bill issued the MRP veto rights over provincial regulations, government agreements with third parties, budget revenue derived from resource extraction; responsibility for nominating candidates for governor, vice-governor, heads and vice-heads of district parliaments, and representatives in the People’s Consultative Assembly/MPR (Agus Sumule Majelis Rakyat Papua—Papua People’s Assembly and its significance in protecting the rights of the indigenous people of Papua, Development Bulletin 59, Asian and Pacific Studies, Australian National University, Canberra, October 2002). For the key points of the seventy-six-clause Papuan draft of Special autonomy, see Special Autonomy Inside Indonesia, Ed 67, July-Sep 2001 (www.insideindonesia.org/feature-editions/special-autonomy).)) And by the time the government actually started implementing the MRP (on 31 October 2005) the MRP had been scarified of credibility and political authority, reduced to a ‘cultural advisory body’ of indirectly selected individuals tasked (only) to approve pre-selected candidates for governor and deputy-governor in the two provinces. ((Individuals are selected—by unknown committees—for election to the MRP—which even contravenes Special Autonomy 2001 and the subsequent Law 32/2004 driven by Yudhoyono (as Minister for Political and Security Affairs).)) As such, the MRP is little more than another layer of leadership designed to complicate the role, and effectiveness of the DAP in particular and the socio-political relations of the independence movement more generally. It lost all credibility after its first chair Agus Alue Alua (a Dani leader from Wamena) was voted to chair the second MRP (2011—), but then found his name (and Deputy-Chair Hanna Hakoyobi) had been deleted from the nomination-list. ((Agus Alue Alua was born on 13 September 1962, two days before passage of Resolution 1752 (New York Agreement) in the UN General Assembly (Agus Alue Alua: A life of dedication to the Papuan People (http://westpapuamedia.info/2011/04/12/agus-alue-alua-a-life-of-dedication-to-the-papuan-people/). He was a key organizer of the Presidium’s 2nd Papuan Congress in 2000. )) As chair of the first MRP (2005—2011) Alua had driven a strong but ultimately unsuccessful campaign contesting the government’s right to create a second province without MRP approval. In 2010 he spear-headed campaign ‘to return special autonomy’ based on an eleven-point critique by his MRP colleagues (who otherwise represented twenty-eight civil organizations). Huge crowds supported the MRP decision, walking seventeen kilometers from Abepura to the DPRD office in Jayapura (as the DAP crowd had five years earlier) on 18 July 2010. Four days after Alua’s death on 7 April 2011, the government divided the MRP into two, one for each province. However the MRP’s work under his leadership succeeded in galvanizing three key churches to (separately) reject Special Autonomy on 26 January 2011 citing ‘tyranny, colonialism, ethnic cleansing and disguised slavery’. ((Theological declaration of churches in Papua regarding the failure of the Indonesian government in governing and developing the indigenous peoples of Papua signed by Elly D. Doirebo M.Si (Deputy-Chair, Synod, Evangelical Christian Church of Papua), Rev. Dr. Benny Giay (Chair, Synod, Papuan Christian Church), Rev. Socrates Sofyan Yoman MA (Chair, Fellowship Papuan Baptist Churches). Available at http://westpapuamedia.info/2011/03/01/papuan-churches-declaration-regarding-failure-of-the-indonesian-government-in-governing-and-developing-the-indigenous-peoples-of-papua/).))

The influential youth movement Komite Nasional Papua Barat/KNPB (West Papua National Committee ) also requires explanation, since it didn’t initially join the Federal Republic of West Papua, but has since recognized its authority (along with Tentara Papua Nasional/TPN, the military wing of the resistance). ((According to Fery Marisan, director of West Papua’s human rights association (ELSHAM), both the KNPB and the TPN bush resistance considered the 3rd Congress agenda in 2011 ‘not radical enough’ (Six dead, many injured and in hiding New Matilda, 20 October 2011).

)) The KNPB is a media unit and non-violent campaign organization established on 19 November 2008 by a number of Papua NGOs seeking a referendum. It has branches throughout West Papua, and in Jakarta and Manado (Sulawesi). In the past eighteen months KNPB members have been aggressively hunted and killed by the Indonesian military, including Chairperson Mako Tabuni who was assassinated on 14 June 2012. Current chair and spokesperson Victor Yeimo was incarcerated (again) on 14 May 2013. ((For a comprehensive report on the treatment of KNPB prisoners see Papua—Prison Island: special in-depth report (http://westpapuamedia.info/tag/knpb/; see also http://www.papuansbehindbars.org) ))

Key structures, Federal Republic of West Papua

i) The Federal Republic of West Papua, a constitution of seven states, believes it represents and has the support of the majority of the Melanesian population.

ii) Active FRWP offices include President and Deputy-President, Prime Minister and Deputy-Prime Minister, State Secretary, Co-ordinating Minister of Foreign Affairs, Minister of Interior, Police Commissioner, as well as state governors.

iii) The FRWP has 35,000 blue-beret police (5,000 in each state); unarmed PETAPA ‘Guardians of the Land’, trained in non-violent techniques, who shadow the Indonesian police when possible, and advise and protect West Papuans, especially during political rallies.

iv) Model for Generation and Re-distribution of Income (based on Freeport’s extraction of gold and copper—which are just two of the nation’s twenty-eight natural resources):

The Federal Republic of West Papua would increase the Effective Income Tax Rate for foreign-owned extraction companies to fifty percent (50%). For example, the $1.3 billion Income Tax paid by Freeport to Indonesia in 2011 would have been $1.5 billion paid to FRWP. ((

Key structures, Federal Republic of West Papua

i) The Federal Republic of West Papua, a constitution of seven states, believes it represents and has the support of the majority of the Melanesian population.

ii) Active FRWP offices include President and Deputy-President, Prime Minister and Deputy-Prime Minister, State Secretary, Co-ordinating Minister of Foreign Affairs, Minister of Interior, Police Commissioner, as well as state governors.

iii) The FRWP has 35,000 blue-beret police (5,000 in each state); unarmed PETAPA ‘Guardians of the Land’, trained in non-violent techniques, who shadow the Indonesian police when possible, and advise and protect West Papuans, especially during political rallies.

iv) Model for Generation and Re-distribution of Income (based on Freeport’s extraction of gold and copper—which are just two of the nation’s twenty-eight natural resources):

The Federal Republic of West Papua would increase the Effective Income Tax Rate for foreign-owned extraction companies to fifty percent (50%). For example, the $1.3 billion Income Tax paid by Freeport to Indonesia in 2011 would have been $1.5 billion paid to FRWP. ((Freeport-McMoran Copper & Gold ‘Expanding resources, 2012 Annual Report’ (p35)

2011: Income 2.9 billion; Effective Tax Rate 43%; Income Tax $1.3 billion; Metal Royalty $137 million (ibid p58)

2010: Income 4 billion; Effective Tax Rate 42%; Income tax $1.7 billion; Metal Royalty $156 million (ibid p59))) $1.5 billion plus the Metal Royalties of $137 million = $1.637 billion, which translates to $935/per Papuan/year ($2.56/per Papuan per day). ((Based on the Papuan population in 2010 of 1,750,557 (Jim Elmslie 2010). )) For 2012 the Income Tax plus Metal Royalties is $2.14 billion, which translates to $1,225.00/per capita per annum ($3.35 per Papuan per day).

Freeport is ramping up production to 240,000 metric tonnes of ore per day (from 165,000).3 This estimated increase of 45% means that in 2017, FRWP income from Freeport would be about 3.1 billion dollars/year, which translates to $1,775 per Papuan per year ($4.86 per Papuan per day).

)) $1.5 billion plus the Metal Royalties of $137 million = $1.637 billion, which translates to $935/per Papuan/year ($2.56/per Papuan per day).2 For 2012 the Income Tax plus Metal Royalties is $2.14 billion, which translates to $1,225.00/per capita per annum ($3.35 per Papuan per day).

Freeport is ramping up production to 240,000 metric tonnes of ore per day (from 165,000). ((Freeport-McMoran Copper & Gold ‘Expanding resources, 2012 Annual Report’ (pp13, 39,40):)) This estimated increase of 45% means that in 2017, FRWP income from Freeport would be about 3.1 billion dollars/year, which translates to $1,775 per Papuan per year ($4.86 per Papuan per day).

Key Priorities

International policy: the Federal Republic of West Papua seeks:

- Recognition by other states and sub-state agencies.

- UN Security Council clearance for registration with the United Nations.

- Third party mediation of negotiations with the Indonesian government (Commission 1) for the removal of its security and political infrastructure. The FRWP believes a regional state agency with international status is better positioned than the UN to mediate.

The FRWP does not seek a referendum, believing it will yield ‘scorched earth’ outcomes experienced by the East Timorese in 1999. However, if the international community believes a referendum is necessary to fulfill self-determination criteria (if not to finalize the New York Agreement), the interests of the indigenous population—in 2010 a minority (48.73%) with an annual growth rate of 1.84% compared to the non-Papuan rate of 10.82%—are stipulated in the FRWP (draft) constitution:

- Indigenous West Papuans will be eligible to vote, the determination of ‘indigenous’ rendered by the chief of the birth-village and witnesses from both the father’s and mother’s families.

- Migrants, non-Papuan wives and husbands, and the children of mixed marriages will not vote in the referendum, precluding any backlash against them should the integration vote prevail.

- After the referendum, migrants and other non-Papuans can choose to become citizens in accordance with the state’s constitutional requirements.

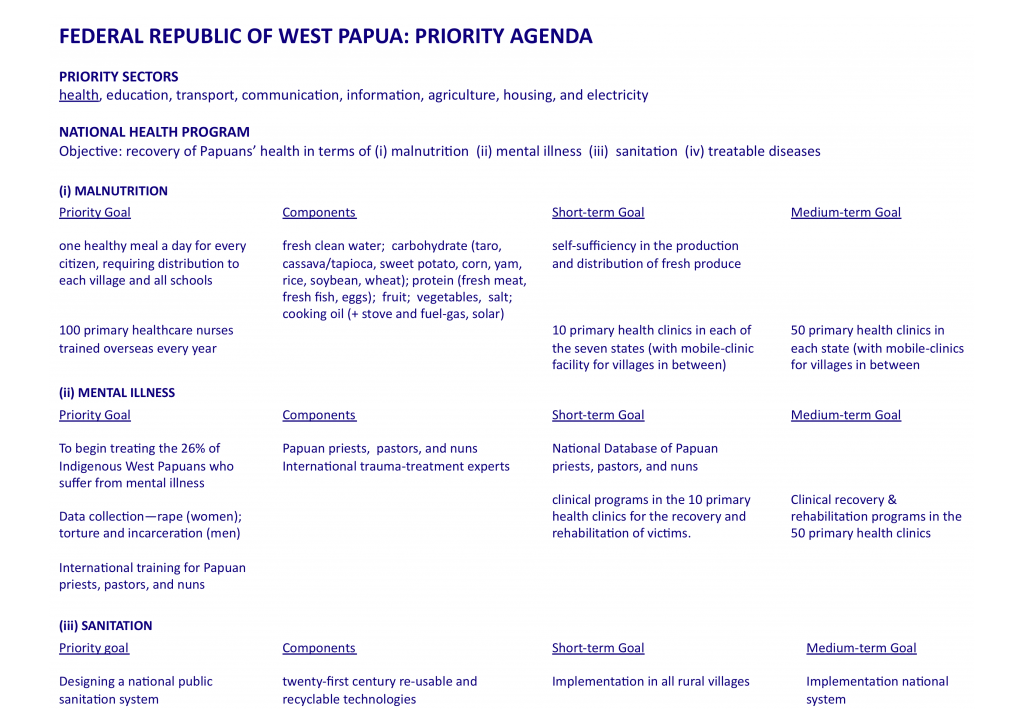

Domestic policy: the FRWP has begun to implement the West Papua National Authority’s social policies (health, education, transport, communication, information, agriculture, housing, electricity).

i) Health: the FRWP believes the recovery of human health is fundamental to its success and stability, and prioritizes the eradication of malnutrition, treatable diseases, and mental illness, and the establishment of a national sanitation system.

Malnutrition: The FRWP will ensure, as part of its national health program, that every citizen has the right to at least one healthy meal a day. Key components of this committment are

i) self-sufficiency within three years in production and distribution of fresh produce— clean water; carbohydrate (taro, cassava, sweet potato, corn, yam, rice, wheat, soybean); protein (eggs, fresh meat and fish); fruit, vegetables, salt; cooking oil (and solar stove).

ii) national distribution system (to each village and all schools, including boarding schools) requiring co-ordination, from the design-stage, with the agricultural and transport sectors.

Treatable diseases: The health index of West Papuans across all indicators is extremely low, even by Indonesian standards. Pragmatically, the FRWP has committed to eradicate, within three years, HIV and AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria, and cholera. Treatment (and education) will be through a network of health professionals in mobile clinics radiating out of the major towns and centres. Data generated will feed back into a central health-management system.

Mental illness: West Papua National Authority research in 2010 demonstrated 26% of indigenous Papuans suffer from various levels and types of mental illness. For cultural reasons, the most difficult to treat will be the socio-emotional effect of rape (for women), and of torture and incarceration (for men). The FRWP seeks to establish teams of Papuan priests and pastors to work with international post-traumatic-stress experts in designing a national program for the treatment education and rehabilitation of victims.

Sanitation: There is no public sanitation system, so independence presents an opportunity to design and implement a national system using the latest reusable recyclable technologies.

ii) Education: for the past half-century, the formal education system has been under-funded, under-resourced, and ineffective because of the politicized curriculum (in state and private schools), lack of older-age technical training (the Papuan indigenous culture accords more respect to the older generation), and the denial of informal (cultural) education. The FRWP is therefore prioritizing:

- holiday-based re-training for Papuans teachers

- teacher-training for primary, secondary, and tertiary level (with an emphasis on the value of informal as well as formal education)

- technical teacher-training programs for cultural custodians

In terms of education infrasture, the FRWP’s priority is to build boarding schools (as well as repair, restock and repopulate the schools that already exist). Community-based weekly boarding schools for primary and secondary school children in the rural regions, can also be used as centres for mature-age technical training and community development centres. While the FRWP believes every student should have a computer with wireless internet coverage, the prioritized emphasis will be on high-quality face-to-face teaching of a culturally relevant and international curriculum.

iii) Transport: the FRWP seeks to develop a ‘green’ national public transport system—on-ground, in-air, and by-water (sea and rivers).

iii) Agriculture: the FRWP plans to facilitate a combination of modern and traditional agricultural systems with a view towards self-sufficiency in food within three years. There are, currently, a few value-added industries (like canned fish and mussel) which should—with product and marketing assistance—be developed for export.

iv) Housing: the FRWP intends to design public housing systems for urban centres that are appropriate for the local cultures and environmental conditions.

v) Electricity: there is currently no national power supply, and no village beyond a few kilometres of a major centre has electricity. Furthermore, the power in the major urban centres is subject to ‘rotating blackouts’ because the boat that delivers fuel every two weeks is often late. Independence offers an opportunity to design, develop and implement a national power supply fuelled by a variety of renewable sources that include solar, wave-energy, and micro-hydro technology.

vi) Rural and urban development: under Indonesian governance, the physical environment has degenerated from an almost pristine status to a filthy combination of land, sea, air, and sound pollution. The FRWP wants to implement a clean (Melanesian-indigenous) aesthetic throughout the nation, firstly by designing for natural parks and public toilets.

Short and long-term development agenda

Social

i) Beyond the normal facilities that citizens have a right to expect, such as schools, hospitals, and correctional houses, the FRWP emphasizes the building of libraries as part of the social education of a people with strong ‘oral’ traditions.

ii) The FRWP emphasizes the need for facilities to cater for victims of a society that has been at war for fifty years, during which time many of the social components of the tribal infrastructure has disintegrated. It therefore needs to plan and build safe refuges for women and children of domestic violence, orphanages for children, and houses for the elderly.

Contemporary West Papua, as distinct from the nation of the 1950s before the Indonesian occupation, is a multi-religious society. The FRWP therefore anticipates creating space for and building mosques, synagogues and temples as well as Christian churches.

Cultural-Economy

The land itself offers an extraordinary capacity for the employment of West Papuans in a variety of sectors, which The FRWP believes can be developed in ways that don’t over-exploite and deplete the fragile (and unique) environment. For instance, the development of farming (buffalo, pigs, goats, deer, kangaroos, cassowary, chickens) and fishing (salt-water, fresh-water, and brack-water) and forest-based plants for medicines.

The FRWP anticipates the development of community-based ecotourism, within which however the cottage craft industry that has mushroomed in recent years (wood-carving, bark-painting, and weaving) will be re-appraised. One of modern West Papua’s most distinguishing features is the culture and traditions of the nation’s 312 tribes, each with its own panopoly of sacred sites, mytho-historical and legal traditions, calendar of nature-based festivals, and music-dance-storytelling repertoire. These need documenting and analysis, with a view to their enabling and application in modern times rather than their (current) treatment as commercial products.

Technical Economy

The FRWP envisages the gradual development of a technical economy, beginning with specialized training in assemblying technologies. Thus, West Papua would buy elements—of the computers, cars, ships engines etc that it needs—from its highly-industrialised neighbours in Asia which specially trained Papuans would then assemble in West Papua.

Law and Democracy

The FRWP does not anticipate imposing the modern laws of democracy, human rights and citizenship in isolation from a serious attempt to transcribe their application across tribal and traditional understandings. This is a big and complex task, but better attempted in the form of a national debate at the beginning of a nation’s existence rather than reverted to when all else fails.

The middle term program will continue the priority programs but with a more outward emphasis—like for example, sending semi-finished products for completion in industrially developed countries, and sending skilled Papuans to help poorer nations around the world.

Author:

Author: