RAYING FOR THE MELANESIAN SPEARHEAD GROUP (MSG)

RAYING FOR THE MELANESIAN SPEARHEAD GROUP (MSG)

ST PAUL’S CATHEDRAL, MELBOURNE

MONDAY 15 JUNE 2015:5pm

Three days before the Melanesian Spearhead Group Summit in Honiara (Solomon Islands), the Revd Heather Patacca is leading prayers at St Paul’s Cathedral in Melbourne. Calling on a motion passed by the Anglican Synod for West Papua’s self-determination, the prayers are to encourage the Melanesian Leadership to accept West Papua’s application for full membership of the MSG in 2015.

The Melanesian Spearhead Group (MSG), comprised of Vanuatu, Solomon Islands, Papua New Guinea, Fiji, and the Kanaky independence movement, was recognised by the United Nations in 2008 as an international organisation. This status renders the MSG the most appropriate forum for political dialogue and conclusive negotiations between West Papua and the Indonesian Government. Indeed, by gracing their Melanesian kin with full membership, MSG politicians will demonstrate their leadership, their dignity, and their sovereignty, as well as enhance their organisations’ status as a UN-accredited International Organization.

Earlier this year, the MSG leaders were tasked by their peoples to embrace West Papua’s application, and provide their long-suffering kin with a seat from which to negotiate peace and justice with Indonesia. The application was prepared by an inclusive, united, representative committee (United Liberation Movement for West Papua) that was elected during the Reconciliation and Unity Summit for West Papuan Leaders in Port Vila in December 2014. The Summit itself was a broad-based initiative to institute negotiations. It was initiated by the 2013 World Council of Churches Assembly in Busan, South Korea; propelled by the Protestant Church in West Papua (Gereja Kristen Injili) and Lutheran Church in PNG; sponsored by the Vanuatu Government; and moderated by the Malvatumauri National Council of Chiefs, Vanuatu Christian Council, and Pacific Conference of Churches.

In the meantime, the Indonesian Government has been attempting, via an array of measures, to derail the process, and most recently presented five of its governors, two of which are West Papuan, as an Associate Member of the MSG. (The two Papuan governors are not freely elected, but are pre-selected as candidates for election by LEMHANAS, a powerful Indonesian institution directly answerable to the President that is tasked to maintain and protect Indonesian ‘territorial integrity’).

On 14 May 2015, PNG Prime Minister Peter O’Neill bowed to President Widodo’s demand for his support, and a week later Fiji Prime Minister Frank Bainimarama followed suite. This is despite their obligations to the MSG Founding Principles ‘to defend and promote independence as the inalienable right of the indigenous peoples of Melanesia’, and ‘to contribute to a peaceful, secure, and stable democratic environment throughout Melanesia’.

Minister O’Neill further diminished himself with incorrect claims that there are eleven million Melanesians in Indonesia, and that the aggregate number of Melanesians exceeds Australia’s population of twenty-three million. Irrespective of this crude opportunism, the issue for the leader of the largest Melanesian state should not have been how many Melanesians live in Indonesia, but how many are dead and dying in West Papua. In 1962, Melanesians constituted 99% of the population in West Papua. By 2010, they’d dropped to 48.7% (1.7 of 3.6 million) with an annual growth rate of 1.8% (in contrast to the non-Papuan rate of 10.8%). According to Jim Elmslie from Sydney University, the Melanesian population of West Papua in 2020 will be ‘a small and rapidly dwindling minority of just 28%’ (West Papuan demographic transition and the 2010 Census: Slow Motion Genocide or not?)

Prime Minister O’Neill said his arrangement with President Widodo would “ensure peace, stability, and development for Melanesians in Papua and West Papua”. Yet just nine days after his meeting with Widodo on 11 May 2015, Indonesian police arrested 70 West Papuans in Manokwari for supporting the ULMWP application; their use of tear gas hospitalizing dozens of kindergarten children. On 28 May, another 46 Papuans were arrested in Jayapura. In March, ULMWP Spokesperson Benny Wenda, who was seriously assaulted in Port Moresby last July, was refused entry into PNG. Markus Haluk, another Papuan leader, was also seriously assaulted in Port Moresby in March, and robbed of the funds collected in West Papua for Cyclone Pam victims in Vanuatu.

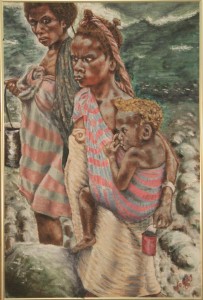

Photo: stain glass window in St Paul’s Cathedral (http://www.stpaulscathedral.org.au/)

This kit is designed to make supporting West Papua’s petition to be registered on the UN Decolonization List easy. It includes background information, flyers, stickers, and documents.

This kit is designed to make supporting West Papua’s petition to be registered on the UN Decolonization List easy. It includes background information, flyers, stickers, and documents.