On 8 December 2016, six students from Melbourne, Monash and Deakin Universities debated West Papua’s status as an independent state. The exhibition debate was hosted by the Federal Republic of West Papua (FRWP) in the Australia Catholic University during the Sampari Art Exhibition for West Papua. The debate was moderated by Dr Jonathan Benney, President of the Debaters Association of Victoria and lecturer in Chinese Studies at Monash University.

The Melbourne University Debating Society, arguing against West Papua’s independence, was represented by Ben O’Shea, Zoe Brown and Alessandra Chinsen. The affirmative team, arguing that West Papua was well prepared to sit amongst the nations of the world as an independent Melanesian state, was led by Kelvin Ka Wing from Monash University’s Association of Debaters, and Joyce Li and Rebekah de Keijzer from Deakin University.

Monash Association of Debaters (MAD) and Melbourne University Debating Society (MUDS) with Dr Jonathan Benney and Lance Collins (Photo-Tommy Latupeirissa)

The Affirmative team, in front of the Sampari Art Festival’s Melanesian Wall of Art (ACU Art Gallery Fitzroy). Photo-Tommy Latupeirissa 8 December 2016

After the debate questions from the audience were fielded by Bishp Hilton Deakin, Lance Collins, Jacob Rumbiak and Isaac Morin. Bishop Deakin is Patron of the Australia West Papua Association (Melbourne) and an influential observer of the important role of Churches and activists in political change. Lance Collins, formerly Lt-Col Lance Collins, was head of INTERFET military intelligence in East Timor between September 1999 and February 2000. Jacob Rumbiak is Executive Officer of the United Liberation Movement for West Papua and FRWP Minister of Foreign Affairs, Immigration & Trade. Isaac Morin, also from West Papua, is completing a doctoral dissertation on Melanesian identity at La Trobe University.

The debate was of a high standard, and well supported by an informed audience that included O’Conroy Doloksaribu from the Indonesian Embassy in Canberra, and Oldrin Lawalata from the Indonesian Consulate in Melbourne. A global audience was able to participate in real time on Facebook. An informal survey of the local audience suggested that if Melbourne University didn’t actually lose West Papua for Indonesia, the Monash-Deakin team presented a convincing case of the former Dutch colony’s willingness and capacity to over-ride Indonesian colonialism.

Media Interview with Jacob Rumbiak before the debate [click to play]

Lunar Flares a composer-performance trio from Footscray opened the evening with an ethereal soundscape punctuated by vocalisations of the text “No war, Lay down your sword of defence, It has no use, What are we fighting for? There’s no war in my home”.

Lunar Flares opening debate with ‘Pigs may fly’ [click to play]

Babuan Mirino, FRWP Womens Office, Welcome [click to play]

WELCOME: “Mandira Bebye. Good evening, and welcome to tonight’s debate. My name is Babuan Mirino and I am President of the West Papua Womens’ Office in Docklands. It’s wonderful to have Australian future leaders interested in our future and I congratulate Melbourne and Monash universities. I feel very happy to be here at the Australian Catholic University surrounded by this amazing West Papua art. On behalf of all West Papuans, here and at home, I thank our brothers and sisters, the Wurrundjeri people, for letting us use their land today. Now, let’s welcome Dr Jonathan Benney to moderate the debate.”

VIDEOS AND TRANSCRIPTS OF THE DEBATE

Jonathan Benney, Introduction [click] debate-transcript-welcome-dr-jonathan-benney

Kelvin Ka Wing Ng, 1st Speaker, Affirmative

[Click for transcript] Debate, Transcript, Kelvin Ng

Ben o’Shea, 1st Speaker, Negative

[click for transcript] debate-transcript-ben-oshea

O’Conroy Doloksaribu from the Indonesian Embassy in Canberra trying to hide his face as he [illegally] records the debate on his mobile telelphone

[click for transcript] debate-transcript-julie-li

Julie Li, Deakin University, in front of entries in the Sampari Art Festival in the ACU Art Gallery in Fitzroy. (Photo-Tommy Latupeirissa 8 December 2016)

Zoe Brown, 2nd Speaker, Negative (video and transcript removed at request of speaker)

Zoe Brown, Melbourne University (Photo-Tommy Latupeirissa 8 December 2016)

Rebekah de Keijzer, 3rd Speaker, Affirmative

[click for transcript] debate-transcript-rebekah-de-keijzer

Rebekah de Keijzer, Deakin University, in the art gallery that was once a horse stable (Photo-Tommy Latupeirissa, 8 December 2016)

Alessandra Chinsen, 3rd Speaker, Negative (video, transcript removed at request of speaker)

Alessandra Chinsen, Melbourne University (Photo-Tommy Latupeirissa, 8 December 2016)

Dr Jonathan Benney, Reflections on the debate

[click for transcript] debate-transcription-reflective-comments-dr-jonathan-benney

AUDIENCE QUESTIONS TO EXPERT PANEL

[click for full transcript] debate-transcript-expert-panel

1. Bishop Deakin, how is Australia implicated in this situation? [click to play]

[Transcript] “First of all I’m not an expert on this at all, but I am an observer of what goes on. I have never been to West Papua except from the other side in Papua New Guinea, and got out again fairly quickly. But I have spent many years in East Timor so I have a very certain taste of the processes that go on. Now if I may say so I enjoyed this debate. I won’t say anything about the man who is making it all possible, but keep it up.

The first thing I want to say is, Don’t let us tell the West Papuans what they should do. Let us discuss it. Let us see it if we want it as a problem for Australia, for the West Papuans, for the Indonesians, and for anybody else. But somehow or another let the West Papuans be the people who want to tell us what they truly want. And you won’t find that by just asking Jacob because he’s only one of them. You’ve got to listen. Listen, listen, listen. And talk. Read of course, and discuss, but don’t come up with solutions. The solutions have to be what the West Papuans want. I make that as the first point that I really want to make.

I want to make another point before I get to this comment about Australia. I think one of the most important features about what is going on in West Papua—not the only one, but a most important one—is the economic factor. None of the debaters said, for instance, that at the western end of New Guinea there is more oil and gas than there is in the Timor Sea. Nobody ever talks about it, but the Indonesians know about it, and they are building ports and arranging facilities for refining and all the rest of it. Now that is the inheritance, if I may eulogize in a way, that nature gave for the West Papuans to have to build their own nation if they want to.

Another thing is that West Papua has one of the richest forest areas in the world. And guess who’s woken up to it? I think the Indonesians have, they’re not stupid at all, but the Malaysians are the people that are picking the eyes out of it. Not too much is being said, but that’s being taken away from the West Papuans as well. If you are going to have the sort of state that requires the jobs and the growth Mr Turnbull and others in this country talk about, you’ve got to have these natural resources to build on.

I used to teach anthropology at university, and I think the cultural matrix that’s in West Papua has to be very carefully understood if you want to understand what the needs of the people are and what their desires and wishes will be. Don’t give them a western one, and particularly don’t give them the hollow one that the Australians reckon they can give. So those are my three warnings.

Now in terms of Australia: what I have experienced over twenty-five years going into East Timor every year for a month or so, is that Australia has got a dreadful reputation in East Timor. Don’t believe what you read in the papers. on’t believe John Howard. That was all a game. Peter Cosgrove didn’t fire a gun except at some of his own soldiers who were disobeying him. The East Timorese went through hell, and they are still picking up bits of bones. When I went in there a week after the end of the war and visited places like Suai and Same, I walked through fields three times as big as the MCG and all I could see were bones. Smelt corpses and blowflies. Hundreds of people who’d been put to death; shot and then tried to be burnt. This was part of the heritage, and it stays with you until you breathe your last. And it will happen also with the West Papuans if things turn out that sort of way. They are the sort of things that require the wisdom of the ages, and also especially I think, humility; to see these people as our brothers and sisters with whom we can work. If they want freedom, yes.If they don’t want freedom, tell us what they want. I have no idea, maybe peace and happiness in a tribal setting … one has to go there and find out and ask the experts on all these sorts of things.

Australia has a very bad, sad, and rotten record with East Timor. I’m fighting in a small way for changes to the maritime boundary between Australia and East Timor. You know, throughout the world, except in Australia, maritime boundaries are straight lines right through the middle. It’s not law, it’s an international practice that has been sanctified because it has happened so often. But Australia won’t do it. They have a boundary that goes something like this, and guess what’s in that area? The oil and the gas that is East Timor’s but which is coming to Australia. Of course, Australia says ’We’ve been very generous with you East Timorese people …we’ve got forty million out of that basin, and we’ve given you four.” But the forty million should have gone to East Timor, the whole jolly lot of it. I’m deeply ashamed when I go to various meetings to discuss this. I am ashamed to listen to the top political figures in this country talking about foreign affairs and the maritime boundary between Australia and East Timor. Believe me, if that’s the way it’s been for the last twenty years, it’s going to be similar when it comes to West Papua, because that’s the only example we’ve got. So we’ve got to think, and re-think all of this and develop a sensitivity and a maturity that I don’t think exists at the present time.”

2. Lance, has West Papua got a chance in hell if they decide to take the military path?

[Transcript] “I want to pause on that question for a moment because I’d like to thank and congratulate the debaters. That was a splendid performance. Well done all around. My only comment is that if you are addressing an international audience you might slow down the delivery, because Australians tend to speak quickly, and even more quickly when we are under pressure—except a former prime minister who had trouble getting words out when under pressure.

I also want to talk a little bit about the independence of East Timor. That happened at a moment in time. For the twenty-four years of the Indonesian occupation from 1975, there was a veil of secrecy drawn over East Timor. Two states in particular were complicit in that. One was Washington, Washington being separate from the American people; and the other one was Canberra, Canberra being separate from the Australian people. And what brought down that three-ways agreement to continue the Indonesian occupation of East Timor was the Asian financial crisis of 1997. That shocked a number of Asian countries, starting with the Thai baht, and then went on to the Indonesian currency, and staggered the entire Indonesian system. And in that moment in time the East Timorese resistance was capable enough and organized enough, and had a foot in the door at the UN where they were able to give the push for self-determination a big shove. And because they had that window of opportunity it actually worked.

For some of the questions raised tonight about how a move to independence or self-determination would go, I was a witness and can attest to the very remarkable goodwill of people from a huge range of countries under UN auspices that did their best to make it work. I echo the Bishop’s comments about Australia’s risable arguments over the seabed boundary with East Timor, but internationally, when there is a moment in time, the international community will step up to the plate on the issues of human rights and self-determination.

West Papua is also a situation in time. When it was originally occupied by Indonesia the world population was something like three billion. It was at the height of the post-World War 2 rise of capitalism, which has now gone on unchecked for seventy years, even if the strains are beginning to show. We’ve had one global financial crisis, people say others are coming, and the results of upset are indicative of what could happen. However, just as no one saw the 1997 crisis coming and the affect it would have on Indonesia, no one can really predict what is going to happen internationally in the future.

So for West Papuan self-determination, the opportunity could come and be fleeting. The record of death speaks for itself. 183,000 killed in East Timor, either killed or died of malnutrition or famine. No one really knows the number of people who have died in West Papua, but the figures range from one hundred thousand which seems conservative, up to half-a-million.

Any sort of out-and-out war there would be very bloody. But the key to it is to keep on with, I believe, the non-violent resistance, because with the advent of the internet and a more globalized counterculture rather than a corporate culture, we are starting to see successes; in Standing Rock, the stand-off in the United States at the moment between Native Americans and corporations over a pipeline, and in countries like Papua over traditional lands.

So the future is hard to predict. Two points that I would want to make. The resort to arms would be a last resort because it would be bloody, particularly without international humanitarian intervention. The second point is that on human rights and self-determination alone, when the opportunity arises, the world will step up to the plate. Thank you.”

3. Isaac, I’d like to hear a bit about the autonomy process. Because my observation was that although it’s promoted to help give West Papua some form of independence, it really has been a process of indonesianization especially as it’s been associated with the transmigration. I think we need to know something about that, and the failure … well not only the failure but the deliberate policy that promoted this autonomy but was really something very different.

[Transcript] “Thank you. First of all I would like to thank the debate teams. This is a real reflection of what’s happening in West Papua, where there are two groups: those that would like to go through Special Autonomy, and others who would like to go straight to independence, both in peaceful ways.

Regarding Special Autonomy. It was started in 2001 by Megwati Sukarnoputri. But it failed, because it contained a clause that says a Papuan representative body, the MRP, had to be instituted first, but it wasn’t until after West Papua was divided into two provinces (in 2005). So the first failure was Megawati’s, because she divided West Papua into two—Papua and Irian Jaya Barat (which is now called Papua Barat). Then the Indonesian security sector suspected Special Autonomy was a golden way, a golden gate, to independence, because Special Autonomy was produced by Papuan academics and Papuan elders who walked around the territory for three months to get the peoples’ ideas. So they never implemented Special Autonomy.

Special Autonomy is meant to be for twenty years. Now it is 2016 and the dateline for evaluation is 2020. But the problem is it has failed. When SBY became president [in 2009], he knew that Special Autonomy had already failed, so he formed a Unit for Acceleration of Development in Papua and West Papua. But that also failed. So when Jokowi became president, he disbanded this program and is using his own approach, which is focused on infrastructure development, even though some Papuans do not like that kind of approach.

When SBY became president, he asked the Indonesian Research Institute (LIPI) to do a very comprehensive research, in an academic, not a political way. Two of the lead scholars were Muridan from the University of Indonesia and Professor King from Sydney University. Both have since passed away, but they designed a road-map for West Papua based on the research. Muridan told The Jakarta Post that when he presented the research results, SBY’s inner circle didn’t accept them, saying that the research was too academic.

4. I lived in West Papua for five years, and since 1983 I have been back another four times, and I haven’t met one West Papuan who wanted to stay with Indonesia. They all wanted independence. What we see on the ground is a lot of very active student groups, military in some of the jungles, the coast, the islands, the highlands, but we don’t see a lot of mass protest. We don’t see sit-ins, or strikes. There are lots of reasons for that, including fear of repercussions, because people do disappear, they get assassinated, and families are intimidated. Isaac, perhaps you could comment on that, in terms of where you think the majority of West Papuans are. The old people have suffered a long time and perhaps are really tired. Maybe they want independence, but they don’t have the energy to push it through or to sacrifice anymore. Or is it that they have given in, and are saying ‘Well if it happens it happens; we’ll leave it to Jacob and a few of you outside to make it happen’. Or is there a simmering resistance, like a lid on a boiling kettle, and it will just take something to take it off and the whole country will erupt.

[Transcript] “Thank you. In West Papua we have two beliefs, two faiths. Number 1, Jesus will come, and No 2, freedom will come. And West Papuans don’t know which one is coming first. More usefully perhaps we can reflect on Donald Trump and on Brexit, because those two phenomena reflect precisely what is happening in West Papua. But until now there is no survey, either from the government or from an NGO. I don’t know why. Maybe they are afraid to have the result, or maybe there’s no funding for doing the research. We don’t know. But if they did a survey, they will see that what happened with Donald Trump in USA will happen, and what happened in Brexit in Europe will happen. Papuans are only waiting for the time. So I think the Indonesian government should do a kind of survey or research so that it has an idea about how to approach West Papua in this case. Because with no survey, I think there is a problem.

We see the phenomena in Jakarta. The governor of Jakarta is Catholic and Chinese, and he’s rejected by most Muslims in Jakarta, because in the Al Koran (Al Qaeda 51) it says that Muslims do not vote for Christians. What happens with elections now in West Papua is that one candidate (of a pair) is Papuan Christian, and the other candidate is migrant Muslim, because there are two populations in the cities. So if there is one Christian candidate and one Muslim candidate, the Muslim will get the vote of all the migrants plus the Muslims, and the Christian will get all the Christian votes but no Muslims. So, for example, if both in a pair of candidates are West Papuan, and another pair is one Papuan and one migrant, this latter one will be the winner. This was happening all over West Papua during the election. So it’s a hard problem to solve, and we don’t have a way, but there is always a way.

5. Jacob, how important is the support of the Pacific nations for West Papua?

[Transcript] “Thank you for the question. I also congratulate the debate groups. The support of the Pacific countries, especially the Melanesian Spearhead Group, is very important firstly because West Papuans are Melanesian, we are not Asian. Recognition of West Papuans as Melanesians puts West Papua on the right track to explain to Indonesia and to the international community that we have a right to independence. The preamble of the Indonesian Constitution says that independence is the right of all nations around the world. So the recognition of West Papua by Melanesians is very important.

Secondly, we go to the Pacific because we want to go the right and noble way. West Papuans cannot negotiate with Jakarta, it is too difficult, we need a third party supported by the Pacific Coalition, especially the Melanesians. That will help West Papua and Indonesia. Our case must be taken back to the United Nations, which is the legitimate international body for solving national problems. Our case is a world problem, because Indonesia’s occupation was facilitated by the international community. That’s why we need a third party. That’s why we go to the Melanesian Spearhead Group. We didn’t want to create another problem between Indonesia and the Pacific. We just want a third party to bring West Papua case to the United Nations; to sit and talk about our future.

The future of West Papua can benefit Indonesia. We are not against Indonesia. The future of West Papua can also benefit the Pacific nations. So that’s our target in going to the Pacific, and of course our work will continue with the Africa Caribbean Pacific group and the United Nations.

[click for transcript] debate-transcript-expert-panel

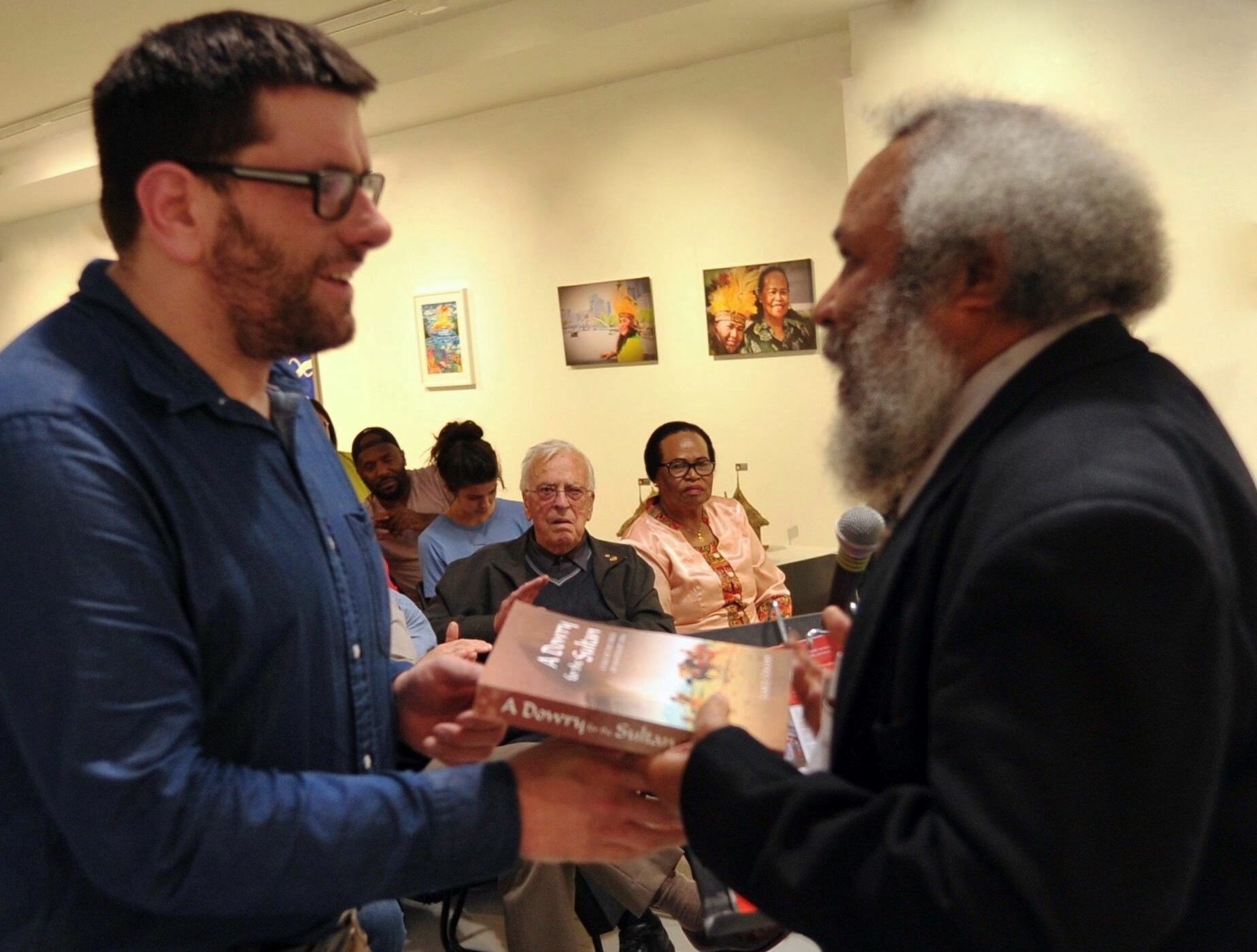

Jacob Rumbiak presenting a copy of Lance Collins’ A Dowry for the Sultan’ to Dr Jonathan Benney (Photo-Tommy Latueirissa, 8 December 2016)

Debaters Kelvin Ka Wing Ng, Ben O’Shea, Rebecca De Kruijzer and Alessandra Chinsen with Louise Byrne from FRWP Womens Office in Docklands (Photo-Tommy Latupeirissa)

NOTES

1. Click for Debate details, debate-details

2. Video Recording and Production: Fredrik Colvio Woirei and Mark Stevens. Live Streaming Jill Koppell (FRWP Womens Office in Docklands). With thanks to Annie McLaughlin from 3CR Radio for audio recording of Lunar Flares.

3. Dr Joe Toscano interviewing Ben O’Shea, 3CR Radio, 23 November 2016 (60′)

4. Bonded through tragedy; united in hope by Jim and Theresa D’Orsa documents and assays Bishop Hilton Deakin’s advocacy for East Timor’s self-determination from the time of the Santa Cruz Massacre in 1991 until the present day. ublished by Garratt Publishing in January 2017 [Click for flyer] Hilton Deakin, A5 Flyer FINAL

5. Suggested Reading: The Murders of Gonzago by Errol Morris. Errol Morris is the Executive Producer of the extraordinary documentary The Act of Killing directed by Josh Oppenheimer about the mass killings in Indonesia in 1965-66 [Click for PDF] The Murders of Gonzago