“Why did Amungme elders put border markers all the way around the Ertzberg mountain of ore in 1967 during the exploration phase? Because that was a sacred area. Indonesian law considers the deep jungle to be empty, to have no owners. This is a very wrong perception. I want to stress that in Irian, there is not a single piece of empty land. Every tree has an owner” (John Rumbiak, Inside Indonesia 47: Jul-Sep 1996)

MT CARSTENSZ (NEMANGKAWI) FORUM

ABUSIVE VISITORS panel discussion on the devastating social and environmental impacts wrought by foreign exploitation of natural resources in Mt Carstensz and the highland communities of West Papua, including rare photographs of Nemangkawi in 1971, 1972-73

SATURDAY 12 DECEMBER 2015, 2 – 4pm

ACU Art Gallery, 26 Brunswick St, Fitzroy

VICTOR LASA Centre for Global Research (RMIT University) with

MUMA YUSEFA ALOMANG Amungme leader from Nemangkawi Word from the Mountain

IZZY BROWN Political activist, Civic journalist Interviewing Muma Yusefa in Jayapura in 2014

RICHARD MUGGLETON Photographer Views of Mt Cartensz, Scientific Surveys in 1971, 1972-73

RALPH PLINER Mountaineer, Corporate lawyer, Chair-Public Interest Advocacy Centre, Sydney Climbing Mt Carstensz, The Seventh Summit

MCHAEL MAINE PhD Candidate, Australian National University Sovereignty, Ownership, and Control of resources: the complexities of cultural-environmental impact and the desire for development and Merdeka

MT CARSTENSZ FORUM, ACU ART GALLERY, 12 December 2015. Victor Lasa, Ralph Pliner, Izzy Brown, Richard Muggleton, Michael Maine

AUDIO: Victor Lasa (4′) Introduction, Mt Carstensz Forum

Victor Lasa, Transcript, Mt Carstensz Forum, 12 December 2015 (click to open)

VIDEO: Muma Yusefa Alomang (10′) Word from the Mountain

AUDIO: Izzy Brown (4′) Answering questions from the audience about her interview with Muma Yusefa

Izzy Brown, Transcript, Mt Carstensz Forum, 12 Dec 2015

AUDIO: Richard Muggleton (17′) Views of Mt Cartensz from Scientific Surveys in 1971, 1972-73

Richard Muggleton, Mt Carstensz Forum, 12 Dec 2015, Transcript and Images

Ekspedisi Ilmiah Puncak Jayakesuma, James Peterson, Hemisphere Nov 1973, Dept of Education Canberra, Ruskin Press-North Melbourne

The Carstensz Massif, AH Colijn, 1936

AUDIO: Ralph Pliner (24′) Climbing Mt Carstensz in August 2001

Ralph Pliner, Mt Carstensz Forum, 12 December 2015, Transcript and Images

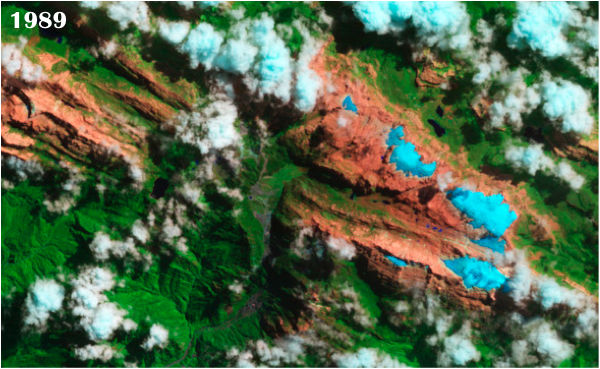

Scientific American, Tropical glaciers in Indonesia may disappear by end of decade, Lonnie Thompson, Aug 2010

AUDIO: Michael Main (20′) Sovereignty, Ownership, and Control of resources: the complexities of cultural-environmental impact and the desire for development and Merdeka

Michael Main, Transcript I’m going to talk to you about some of the broader issues around mining in Melanesia, and Papua New Guinea more generally. PNG is a country very dominated by the activities of multi-national mining corporations. I want to get into the complexities of that issue, socially, economically, and environmentally.

These are two photos I took of the Fly River. One is upstream of where it intersects the Ok Tedi River that carries the pollution from the Ok Tedi Mine. And the other is below the Ok Tedi River. So they are two photos of the same river taken a few kilometers apart. Ok Tedi is very similar to the Freeport mine in that it’s a copper-gold mine that disposes of tailings directly into the river.

Fly River upstream from the Ok Tedi Mine on the Papua New Guinea border with West Papua (Photo: Michael Main)

Fly River downstream from the Ok Tedi Mine on the Papua New Guinea border with West Papua (Photo: Michael Main)

According to Joseph Stiglitz, the former chief Economist at the World Bank “In the ideal world of a globalised competitive market, mining companies should be considered as part of an extraction service industry, with all the remaining value of the resource over and above the cost of extraction going back into the country.”

Of course in the real world of globalization this could not be further from the case. As players in a competitive world, Stiglitz tells us, trans-national companies undertake to make sure sovereign governments get as little of their resource wealth, while simultaneously claiming the enormous social benefits and development that mining is supposed to bring.

The story of mining in Melanesia over the past few decades is very much a version of the type of world that Stiglitz was warning us about. Environmental destruction on an epic scale at Ok Tedi, civil war at Bougainville, murder, rape, and a state-of-emergency at the Porgera Mine, an acid lake in declining socio-economic conditions at Misima, are all far removed from the claims made in the glossy brochures produced by the mining companies.

Now the current economic crisis being faced by Papua New Guinea is due in large part to policies that favour the mining industry over other forms of economic development. At the same time, the PNG economy has become more dominated by resource extraction projects than ever before. PNG is facing the biggest fiscal crisis in its history. According to Paul Flanagan of the Development Policy Centre, this is largely due to the fact that mining companies are taxed more lightly than other industries. The average tax-rate for the resource sector is currently around ten per cent, with huge tax concessions and falling commodity prices combining to produce the resource-curse nightmare that has affected many other resource-rich developing nations.

Added to this macro-economic failure, is a legacy of environmental destruction, rampant corruption, and failed promises of development that has seen Papua New Guinea fall below Zimbabwe on the UN Human Development Index.

But it’s a mistake to view issues of resource extraction solely through a lens of environmental impact. In the Melanesian context, mining projects are overwhelmingly desired by indigenous populations, because mines are being seen as capable of providing badly needed health services, well equipped schools, roads that will connect remote areas to markets, fresh water supplies, houses that ease the labour burden of constant repair. And all of this in a context where the state is viewed as both unwilling and unable to provide.

Kaikok, a West Papuan refugee village on the Fly River, caked in tailings from the Ok Tedi mine (Photo: Michael Main)

This is a West Papuan refugee village, Kaikok, on the Fly River, that’s caked in tailings from the Ok Tedi mine. Even along the heavily polluted Fly River, I was told by West Papuan Muyu refugees that the Ok Tedi Mine was good for the country. And they were talking about a country that refused to acknowledge that they even exist. What they wanted was access to markets so they could sell whatever they could produce.

When I was among the Huli people in 2009, when Exxon Mobile was scoping out their massive liquefied natural gas project, the level of excitement and anticipation of what was assumed to be the beginning of a new and wonderful era for Huli people, was overwhelming. Other researchers have documented the willingness of local people to give over their land to mining companies, including Martha MacIntyre for Lihir, Alex Golub for Porgera, and several others. Jerry Jacka has recently documented the ways in which the terrible social and environmental impacts of the Porgura Mine, has led many Porgurans to desire even further mining as a way of developing themselves out of their current problems.

For those of us who are appalled by the mining industry’s disastrous environmental track record across Melanesia, the reality that most of this mining activity has been desired by indigenous populations is a difficult pill to swallow. West Papuans who were agitating for independence from their base in Kiunga, told me that the ore at Mt Cartstensz was given to West Papua by God as a resource to help them develop their country once merdeka had been achieved.

Catholic Aid Post in a West Papuan refugee village near Gumban on the Fly River (Photo: Michael Main)

So what’s the point of all this? If multi-national mining companies are ever going to be prevented from causing such destruction to both indigenous societies and the environments in which they live, then we must not view indigenous peoples as environmentally noble savages stuck in some idealized pre-modern existence outside of history, and free from a common human desire for change. The environment is a concept that is imaged in vastly different ways by different people in different settings. And none of us have a monopoly on how the environment should be perceived. Perceptions of the environment cannot be separated from other experiences of life, including those related to economics, politics, religion, education, health, and increasingly, electronic communications.

Now it’s this last point I think holds the key to achieving a just outcome for the indigenous peoples of the world when faced with the ever-increasing risk of neo-colonial multi-national mining corporations. For many indigenous peoples across Melanesia and other parts of the world who are desiring educational opportunities for their children, lower rates of infant mortality, safe drinking water supplies, the prospect of a mining company delivering on these promises is the only game in town. The failure of states to devise economic policies that encourage diversity and the sustainable use of local resources is one of the main reason why mining companies have been able to extend their operations into more and more of the world’s indigenously owned land. It is too easy for states to out-source their responsibilities to mining companies, who make glossy promises of development and sustainability in their brochures and websites. And the opportunities for graft and corruption further reduce the amount of resource revenue that can be used to improve people’s lives.

In my opinion, the best way to prevent the widespread view that a mine is needed for development, is for information about the complex reality of the impact of mining, and the alternative ways in which states can devise development policies that don’t rely on a resource-extraction economy, to be made available to indigenous populations across the globe. It is my hope that the spread of electronic communications will connect the world so that the people will be able to make choices that are better informed and agitate for the political changes needed to improve their lives.

Grass-roots opposition to sea-bed mining proposal in the Bismark Sea was aired at The Rio+20 Conference on sustainable development Rio de Janeiro in June 2012 (http://www.deepseaminingoutofourdepth.org/stop-ocean-crime-banner-for-rio20/)

I was asked to talk about examples where mining companies have been prevented from operating. From my perspective, the most interesting thing going on now in this regard is the widespread grass-roots opposition to sea-bed mining that is being proposed for the Bismark Sea. According to Colin Filer at ANU, this opposition has a deeply religious basis, and often includes the argument that sea-bed mining is against the Book of Genesis. No such argument is made against land-based mining in PNG. Even the people of Lihir raise no opposition to waste from their mine being dumped into the sea off their island. The nature of the sea-bed is being imagined quite differently to land-based nature.

As an anthropologist, this is quite fascinating. Is it because no one other than God is seen as owning the sea floor, and therefore no one has any right to sell it off? Is it because mining the sea-floor can’t be directly associated with development: you can’t build a hospital under the ocean. Is it because people are better informed than ever before, and the technology for sea-bed mining has come about at the same time as informed ideas about mining have become more widespread, and people have decided to draw a line.

Of course the answer is a complex combination of all this and more. If the response by the state to opposition to a mine is to send in the army and shoot you, then the dissemination of and access to information only becomes more vital.

The fact that this can happen in the 21st century on Australia’s door-step means that awareness and exposure of the sustainable resources must be deployed against the unsustainable belief in the supremacy of mining as the gold-stand of nation-building and development.

VICTOR LASA Thank you Michael. All the speakers were under pressure because I said they could only have twelve minutes. You’ve done very very well.

It is very interesting to understand the complexity of mining activities, the role of government, the role of populations. I always wonder though about the role of the private companies doing the mining. I mean, they know how to do mining right, as in respecting environmental laws, respecting social justice, and being good for nation-building. Why does it change when they go to what we call a developing country? What makes it different that they don’t seem to care, and they feel they can do whatever they want and nothing happens. Is it just corruption?

MICHAEL MAIN It’s a real mixed bag. People have tried to do ethnographies on mining companies themselves. They have their own unique personality. The attempt to do the right thing is largely driven by the finance industry. You can’t get finance to proceed with these mines without having all the requisite environmental and social reports, and all that sort of stuff. But often that’s just box-ticking of course. Some mining companies think that they are … they believe in the neo-liberal rhetoric and actually think that they can do well. But mining companies don’t know how to build nation-states. That’s not what they do.

Exxon Mobil is an interesting case, because it is such a huge company that it has never required external finance for any of its operations, and it has never had to answer to any lender. The LNG project, because it’s in partnership, is the first time that that it has actually had to deal with these requirements. And it’s a shoe that doesn’t fit Exxon Mobil very well.

VICTOR LASA Many people are expecting corporations to do development work, either governments or NGOs. But they might not know how to do it, or they might not have any interest, so putting that work in their hands is dangerous. Are there any questions for Michael please?

AUDIENCE I come from a mining business in Papua New Guinea. And I grew up when the mine came. And many people thought about mining, but not about the exploitation and the environment damage. And they don’t know what they do. I witnessed from childhood up to when we stopped the mine. And I think that one of the issues that Bougainville—I’m from Bougainville—we took up is the environment. So when we talk about the environment and environmental status, not even the mining company want to do it, because they don’t want the people to take them to court, because they will take a lot of money for the attempt.

So that’s one of the biggest problems in PNG now, is that people …well in my situation, my people were never asked, because we were a territory of Australia, and they sent the Federal Police, and told the chiefs, with guns, ‘You sign, or else you go to jail because you are breaking the law’. So that’s what happened. After then after, we got educated, and we knew what they did to our fore-fathers and our fathers. And we took the fight. I was one of them who was at the university in PNG. I went for campaign, and said ‘This has to stop. No matter how we are going to do it, we’ll do it.’ Then the army was sent. We fought with bows and arrows, we killed people, we got the guns, then we started fighting. We closed it unless you get the environmental study. We want to know how much damage.

So from childhood up to now I know exactly what happened. Where I grew up, where we used to go playing around fishing, I could see it gradually degraded. So I see how much damage it can do. But it’s greed, also our politicians, they get the money, the don’t worry about the people. So I’m actually organizing some top lawyers who I met in Sydney to go and fight with Rio Tinto. They can do it, and then we will get the environmental study done. That’s what we want. So we know exactly how much damage they’ve done.

PANEL MEMBER Can I actually ask you a question? What advice would you have, from your experience in Bougainville, for the people in West Papua around the Freeport mine?

AUDIENCE We’re already involved with the West Papuans. We met them, and when they come, they go onto Vanuatu and the Solomons. So we help them at any time. We support their cause, because we are in a similar situation. I think there is a lot more public awareness, which is important. People need to know the figures and statistics about what actually happened. That’s why it’s difficult in West Papua because the US and the Indonesian Army, they won’t let anyone go there and study the damage. Whereas we are in a better position to do it, because the Bougainville Government just ….. I don’t know if any of you have read it … they have a parliament and then they pass a mining law. But we are questioning the mining law, because it was written by the World Bank to suit the developers. So we are publicly campaigning against it, because people …. I don’t know if you know Joe Bili … well they just went and did some report. They said the mining law is shaky because ….our president says that it will help the landowners, but if you read it, it’s not going to help. They said the landowners will have the last say, but that’s not true. Yea, so we are doing a lot of public awareness. That’s the important thing. What West Papua is doing is good. They can go across the world and push the agenda on the environment. Because our environment is gone. The future kids and grandkids that come in, they won’t have anything. They’ll be born into chemicals, and you know, they won’t be healthy.

VICTOR LASA Thank you very much for your contribution.