Introduction

On 1 October 1962, the Netherlands Government transferred the administration of West Papua to the United Nations. Six months later, on 1 May 1963, the UN transferred the administration to the Republic of Indonesia. At the time the Indonesian government claimed it wanted to free West Papuans of Dutch colonization, and promised to develop West Papua. However, between 1963 and 1969, the dignity of the Melanesian people was undermined, and their human, political and environmental rights were abused; a situation that endures to the present day.

To protect West Papua rights and resist the neo-colonial impunity of the Indonesian state, the OPM (Free Papua Organization) was established in 1964. The resistance struggle has a military wing (the West Papua National Liberation Army/WPNLA), and intelligence, political and diplomatic wings. Conservatives estimate that more than 100.000 Papuans have disappeared or been killed the Indonesian military since 1963 (Budiardjo, C and Liem Soei Liong, West Papua—The obliteration of a people). Thousands of Papuan women have been raped, and activists are regularly kidnapped and imprisoned, or sent into exile. In 2007 forty-three Papuans escaped to Australia seeking political asylum. They are visiting Parliament in Canberra today to tell Australian politicians that West Papuans have endured Indonesian the government’s genocidal policies, terrorist activities, and intimidatory tactics for forty-four years.

When the period of ‘reformasi’ began in May 1998, the majority of Melanesian West Papuans demanded the reinstatement of the political rights stolen by the Indonesian government and the 84 member-states of the United Nations when they validated the ‘Act of Free Choice’ in 1969 (which Papuans continue to describe as the ‘Act of No Choice’).

On 26th February 1999, a hundred-member delegation of West Papuans met the then third President of Indonesia, Prof. Dr. J.B Habibie, at the Presidential Palace in Jakarta, requesting justice and peace and separation from the Indonesian state. President Habibie responded by telling them ‘to take time and think about it’. A few months later, the Papuan Second National Congress, (29 May—4 June 2000), meeting in the capital city of Jayapura, issued a statement reiterating their right to separation from the Unitary Republic of Indonesia. The government’s response was to impose Special Autonomy on the West Papuans, and to explain to the international community of donars that demands for independence were underpinned by social and justices problems.

However, most international analysts claim that Special Autonomy has failed in all the regions in Indonesia, and especially in West Papua (Indonesian Research Institute/Lembaga Survei Indonesia/LSI, 19 March 2007). LSI’s research shows that two years after the imposition of Special Autonomy, less than 10% of Special Autonomy laws have been implemented in West Papua. An earlier report, to the British Council in 2003, articulates the legal, political, and administrative problems associated with Special Autonomy (Sullivan, L. Papua’s special autonomy law and the issues of division, 10 September 2003; this paper was also presented to the Australian National University in September 2003). The author, Laurence Sullivan, was seconded from the Legal Office of the Scottish Government to the British Council and sent to West Papua for one year in 2003 to examine parallels between devolution in Scotland and Special Autonomy in West Papua. On 12 August, 2005 the civil society sectors in West Papua sent Special Autonomy back to Jakarta, the city where it was formulated and from where it was instituted.

On 3 July 2003, the Indonesian newspaper ‘Sinar Harapan’ published the results of a survey conducted by the International Foundation For Election Systems (IFES) in association with an international research institute, the Tyler Nelson Survey (TNS). Survey results suggest that more than 75% of Melanesian West Papuans want independence from the Unitary Republic of Indonesia. Another survey by the West Papua National Student Union in 2001, conducted at the request of the International Commission of Jurists in Australia, showed that more than 95% of Melanesian West Papuans want independence from Indonesia.

On 10 July 2007, the Indonesian newspaper ‘Suara Pembaharuan Daily’ quoted Prof. Dr. Muladi, Governor of the Institute of National Defence of Indonesia, as saying “special autonomy offered by the government of Indonesian to Papua is a strategy to retard the Melanesian West Papuan rights to independence”. It is clear to most international analysts, and especially to Australian politicians (both the government and opposition), that special autonomy is not the solution For West Papua. The Indonesian government is employing all kinds of strategies, including military arms and covert intelligent operations, to block West Papuan rights, including demonstrations of their readiness to operate as a nation-state separate from Indonesia. According to Professor Muladi, the West Papuans have capable human resources, a wide network of support in the international community, and a transition government which is already operating.

In 2000, the West Papua National Authority which has been developing clandestinely since the mid-1980s, brought together the key Papua organisations (including the OPM, Presidium, and West Papua Liberation Army) within a comprehensive infrastructure for resistance, and for governance beyond the Indonesian occupation (Awawi Agreement, 2000). In 2007 the Authority achieved a major objective when it signed a memorandum-agreement with the Manuariki Council of Chiefs in Port Vila for the Vanuatu nation to take responsibility for relisting West Papua on the UN Decolonisation List.

The West Papua National Authority believes its primary role for 2008-2009 is to work with the international community is delivering safety and security in West Papua for the discussion of a future based on democratic principles within an atmosphere of truth-seeking justice, peace and love.

Is there a credible, united West Papuan leadership in place?

In February 2002, in Wewak on the north coast of Papua New Guinea, 89 key political leaders and activists from Organisasi Papua Merdeka (OPM), Papua Presidium Council (PDP), and the West Papua New Guinea National Congress formed the United West Papua National Council. The meeting was partly auspiced by Sir Michael Somare (former Prime Minister of Papua New Guinea), and the recently-deceased Sir Tony Bais, another founding father of PNG.

The Wewak meeting in 2002 was instigated partly in response to confusion surrounding the 2001 Pacific Island Forum in Nauru, to which three West Papuan organizations sent delegations. The United West Papua National Council provided a channel for West Papuans to voice their political aspirations. It was structured so as to clearly delineate responsibility for, and boundaries between human rights, peace and justice, and traditional customary issues.

Two years later, in Wewak, in June 2004, a specially convened meeting of the West Papua National Council brought about the formation of the West Papua National Authority. The National Authority has executive, legislative and judiciary bodies, and is the national umbrella body for bringing about unity, awareness, and reconciliation between West Papuans; for promoting self-determination and independence to the international community; and for devising strategies with Jakarta for the peaceful resolution of the independence issue.

The National Authority is particularly concerned to maintain unity between the leadership inside and outside West Papua, not only between those who are prominent in the national (Indonesian) and international arenas, but also between the tribal leaders, the NGO and religious sectors, women and the student organizations.

It needs to be noted that the West Papua National Authority is the national carrier of West Papuans’ political aspirations and strategies. Other organisations provide other services. Elsham, for instance, is the national organisation for the carriage of human rights issues. Churches and NGOs provide passage for the implementation of peace and justice. The Traditional Council is the forum for discussion and determination of indigenous issues.

The public faces of the West Papua National Authority:

Speaker, National Congress:- Rev. Terrianus Yoku, a Protestant pastor in Sentani (Jayapura). Pastor Yoku is an ex-political prisoner, and member of the Papua Presidium.

President of the Executive:- Edison Waromi, S.H., a lawyer, political prisoner, and long-time member of West Melanesia National Council and Organisasi Papua Merdeka. He was incarcerated by the Indonesian government 1989-1999; and again in 2001, 2002, and 2003-4.

West Papua representative to the United Nations:- Rex Rumakiek, M.A., long-time spokesperson for the OPM, and current Director of the Pacific Concerns Resource Centre in Suva, Republic of Fiji Islands.

Supreme Commander, West Papua National Liberation Army:- Brigadier-General Richard Joweni.

Co-ordinator, Foreign Affairs:- Jacob Rumbiak, former lecturer in the physical sciences at Cenderawasih University, political prisoner, long-time member of Organisasi Papua Merdeka, and founding member of the non-violent campaign for independence. Currently, living in Melbourne.

The West Papua National Authority has 32 departments, with political and technical specialists.

Are the West Papuan people united in their desire for independence?

It should be noted that the decision made in 1969 by certain individuals purporting to vote on behalf of all Papuans—to accept integration into Indonesia—was a process that has long since been discredites. ((The UN-supervised vote by 1,025 so-called representatives has been demonstrated to have been manipulated by the Indonesian military-government (The United Nations and the Indonesian Take-over of West Papua, 1962-1969: The anatomy of betrayal, John Saltford, Routledge Curzon, London, 2003). ))

On 3 July 2003, the Indonesian newspaper ‘Sinar Harapan’ published the results of a survey conducted by the International Foundation for Election Systems (IFES) in association with an international research institute, the Tyler Nelson Survey (TNS). Survey results suggest that more than 75% of Melanesian West Papuans want independence from the Unitary Republic of Indonesia. Another survey by the West Papua National Student Union in 2001, conducted at the request of the International Commission of Jurists in Australia, showed that more than 95% of Melanesian West Papuans want independence from Indonesia.

The non-violent campaign for independence, launched in 1988, has unified West Papuans, and galvanised civilian resistance in the cities and towns. Based on justice, peace, and love, the campaign has motivated women and students to organise and mobilise. It has also provided an avenue for civil servants, the religious, academics, and transmigrants to politicise their aspirations while not necessarily appearing to contravene central government policy. ((The ‘state of emergency’ in January 2004 is the government’s response to widespread support for independence. Academics, religious leaders, and civil servants, are subjected to extreme levels of intimidation, and on 20 January, four prominent West Papuan political moderates were forced to flee Indonesia clandestinely.))

The non-violent movement has also inspired the leadership of the Christian churches to co-operate. In the mid-’nineties, the Protestant Church, Roman Catholic Church, the Pentecostals and Evangelical Churches formed one Fellowship. ((Important Christian religious organizations in West Papua include the GKI (Gereja Kristen Injili of Irian Jaya) who origins are in the German Lutheran Church and the Dutch Reformed Church; the Roman Catholic Church; the Christian and Missionary Alliance (CAMA); Missionary Aviation Fellowship; Seventh Day Adventists; Regions Beyond Missionary Union which set up the KINGMI Church; Evangelical Alliance Mission or TEAM which has origins in Britain and Europe and which established the GKAI/Gereja Kristen Alkitab Indonesia). )) They are working closely with indigenous Papuan Muslims (predominately from Fak Fak on the south coast) and Muslim organizations representing Indonesian Muslims in West Papua (for example, transmigrants, free settlers, public servants, and the military).

Two groups in West Papua that take no part in the independence movement are the militia, and the free settlers who dominate the economies in the towns. Many free settlers may wish to leave voluntarily if changed political conditions interfere with their commercial enterprises.

How ready is West Papua for independence?

Currently, the head of almost every department in the Provincial administration is West Papuan. There could, therefore, be a smooth transition of power from Indonesia to West Papuans providing the international community ensures there is not a repeat of the Indonesian military’s behaviour after the referendum in East Timor.

The territory’s wealth of natural resources would indicate a strong potential and major possibilities for West Papua to be economically viable. The Papuan political leadership is keen to begin negotiating directly with the trans-national companies, because of the enormous disparity between the wealth that goes to Jakarta and the amount paid to the province by the central government.

The accounts of the Freeport mine are illustrative. Taxes paid by the company to Jakarta in 2002 included income tax ($us186.5 million) and deferred tax ($us49.1 million); a total of $us235.6 million. If the combined royalties for all metals was included ($us24.5 million), the total would have been $us260 million. ((Freeport Annual Report 2003. www.fcx.com: pp 53,45.)) Against this, the Indonesian government’s official expenditure budget for the province of West Papua for the following year (2003) was $us97 million.

It has been suggested by some foreign analysts that an independent West Papua would descend into communal violence and tribalism, perhaps in the direction that Papua New Guinea is in danger of heading. However, these analysts short-change the West Papuans, who have watched and learned from the independence experience of their Melanesian kin in the Pacific. These analysts also fail to acknowledge how much of the West Papuan identity is a result of the experience of being an Indonesian colony. One of the great strengths of the Papuan identity is an appreciation of the nation’s diversity—not only of the indigenous cultures, and numerous races, but also of religious beliefs (especially the harmony between Christians and Muslims).

What will be the form of the West Papua nation-state?

There has been much discussion and debate amongst West Papuans about the form of their nation-state. Broadly speaking, West Papua will be a presidential democracy, constituted by the current administrative zones and by clan group representation. It is envisaged that for a number of years, a traditional stream of democracy (enabling tribal leadership representation) will operate alongside a modern system of political party representation. The state will be organized around conventional branches of government with an executive, legislature, and judiciary.

Once independence has agreed upon, then steps will be taken to ensure the full consultation and involvement of all West Papuans in the adoption of an independent constitution. The constitution already adopted by the United West Papua National Council for Independence and the West Papua National Authority foreshadows the spirit and structure of such a constitution.

How will transmigrants fare after independence?

The constitution of the West Papua National Authority guarantees to protect the civil rights of all people living in West Papua, including ‘foreign permanent residents and foreign temporary residents in West Papua’. ((Principle Regulations of the West Papuan Struggle for Independence, United West Papua National Council for Independence, Chapter XI, Article 54.)) The Second Papua Congress in June 2000 resolved to protect and guarantee the civil rights of all people living in West Papua, including the minority groups. It also resolved to respect all people, with no discrimination on the grounds of tribe, religion or racial group. ((Resolusi Kongres Papua II, p.3. )) All West Papuans, through indigenous NGOs (including religious, student, academic, women, environmental, and human rights organizations) support the declaration of their territory as a ‘zone of peace and justice’ first enunciated by the West Melanesia National Council in 1988. West Papuans have consistently called on Jakarta to respect this declaration that emphasizes the dignity of all human beings and the environment.

Papuan activists began work in 1982 to overcome difficulties between transmigrants and indigenous Papuans. Generally speaking, most transmigrants (as distinct from free settlers) consider their future is in West Papua, and are actively supportive of the independence movement. In 1999, Dr Abdul Gofur, a member of the Indonesian National Parliament (and Minister for Youth under President Suharto) led a delegation to West Papua to investigate relationships between the two races of people, and found 87% of non-Papuans in West Papua support independence. Amber/strangers, an organization of transmigrants with an independence platform, was formed in 2000 and has since spawned other similar organizations, including ‘Kelompok Pemuda Amber/ Immigrant Youth Section’.

Most transmigrants have a Papuan ethos, appreciate the harmony between the majority Christians and minority Muslims in West Paua, and relate to the Papuan political elite who have regulated against all forms of discrimination. The considerable number of Javanese women married to West Papuan men are often described as “more Papuan than the Papuans” and consider their relationship with indigenous Papuan Muslims as more meaningful than relationships with Muslims in Jakarta and the rest of Indonesia.

What is the attitude of West Papuan leaders to transnational corporations?

West Papuan independence leaders consider foreign investors should be seeking relationships with them, rather than trying to secure arrangements with the Indonesian government—which, according to several Javanese parliamentarians, has lost control in West Papua anyway. The West Papua National Authority is willing to negotiate with foreign investors, subject to recognition of the indigenous cultures and human rights, and the company’s active (negotiated) participation in protection of indigenous flora, fauna, water, air and land.

Agreements reached between the company and the Papuan nation-state will be based on the principles of truth and justice, and real, not perceived sustainability of the Papuans and their eco-system. The issues of royalties and state taxes, and development of local education and health will be negotiated through the offices of the state and in consultation with the indigenous tribes of the affected area.

The failure of special autonomy

Special autonomy in all the regions in Indonesia, and especially in West Papua, has totally failed (Indonesian Research Institute/Lembaga Survei Indonesia/LSI, 19 March 2007). The Institute’s research shows that two years after Special Autonomy was legislated, less than 10% of the law has been implemented in West Papua (Sullivan, L. Papua’s special autonomy law and the issues of division, Sept 2003). Laurence Sullivan was seconded from the Legal Office of the Scottish Government to the British Council, and sent to West Papua for one year in 2003 to examine parallels between devolution in Scotland and Special Autonomy in West Papua.

Knowing and understanding the roots of the problem

(a) To occupy West Papua, the Indonesian military government manipulated history and lied to its own national community and the international community, by saying that:

1. West Papua should become part of the Indonesia Republic because West Papua was part of

the Majapahit Empire which existed between 1293 and 1520.

2. The Sultan of Tidore in North Moluccas always claimed the Raja Ampat archipelago off the West Papuan Birdshead, so the same region should also be part of the Unitary Republic of Indonesia.

3. All colonies of the Dutch East Indies were part of the Unitary of the Republic of Indonesia.

4. The Dutch would use West Papua re-claim control over the Indonesian archipelago.

(b) On 19 December 1961, President Sukarno launched a military operation ‘Tri Kommando Rakyat’

(Peoples’ Three Commands) led by Major-General Suharto against Dutch New Guinea.

(c) West Papuans were not consulted during New York Agreement of 1962 that was designed by

America to solve the dispute between the Dutch and the Indonesians over West Papua.

(d) The administration of West Papua was transferred by the United Nations to the Indonesia military-

government on 1 May 1963 without a referendum.

(e) The Act of Free Choice in 1969 used Indonesian, not internationally-accepted practices. ((Departemen Penerangan Republik Indonesia. Pepera di Irian Barat, Jakarta, 1969:491))

(f) Industrialized countries (like the United States of America, United Kingdom, Holland, and Australia) still believe that the Indonesian military-government will develop West Papua through Special Autonomy which was to be implemented in January 2001. The people of West Papua have thoroughly rejected Special Autonomy, and the Indonesian government undermined its own Special Autonomy program by partitioning the province, firstly into three (and later four).

Rebuttal of Indonesian claims

West Papua was never part of the Majapahit Empire.

The Majapahit Empire under King Hayam Wuruk (or Rajasanagara) existed between 1293 and 1520. It was based in East Java, and included two thirds of Java Island, some of South Borneo and South Celebes, Western Lesser Sundas, and Eastern Lesser Sundas to Central Moluccas. (( Ronald Laidlaw, Asian history. McMillan Company of Australia, 1982:225.)) The Majapahit empire did not include Madagascar in West Africa and the Pas archipelago off the coast of Chili—a claim made in all Indonesian documents, including school curriculum texts. There is no evidence that the King of Majapahit conquered territory in West Papua.

If Indonesia claims its occupation is legitimate because West Papua was part of the Majapahit Empire, why didn’t Indonesia also claim territory between Madagascar Island and the Pas Archipelago—which Indonesia also claims was part of the Majapahit Empire? If the Majapahit did control the huge stretch of sea and islands between Madagascar and Pas—as Indonesia claims—we must conclude that the Majapahit Empire, like the Unitary Republic of Indonesia, was an aggressive colonizer.

West Papua territory was not part of the Sultanate of Tidore.

In 1660, the Sultan of Tidore told the Dutch East Indies Company that West Papua territory was under his control. (( Lagerberg Kees, West Irian and Jakarta Imperialism, London, Hurst, 1979:16.)) Four centuries later, Ir Soekarno used this history to claim the same territory for Indonesia—conveniently ignoring the fact that in 1679 the Dutch governor of Banda Island, Mr Keyts, suggested that the Sultan’s claims should not be taken seriously. Sokearno also ignored public statements by Captain T Forrest in 1775, and the governor of Ternate in 1778, that the Sultan of Tidore had no power in West Papua and no claim over the territory. ((ibid)) Soekarno also ignored the writings of Dr. FC. Kamma, a Dutch priest and anthropologist who worked in West Papua in 1940’s, who said that Kurabesi, hero of Biak and Numfoor marine warriors, married the Sultan of Tidore’s daughter—but that such a marriage could only have resulted from a successful invasion by Kurabesi of the Sultan’s territory. (Some Biak-Numfoor people, like my mother, still have land in Tunuwo in Ternate-Tidore resulting from the marriage).

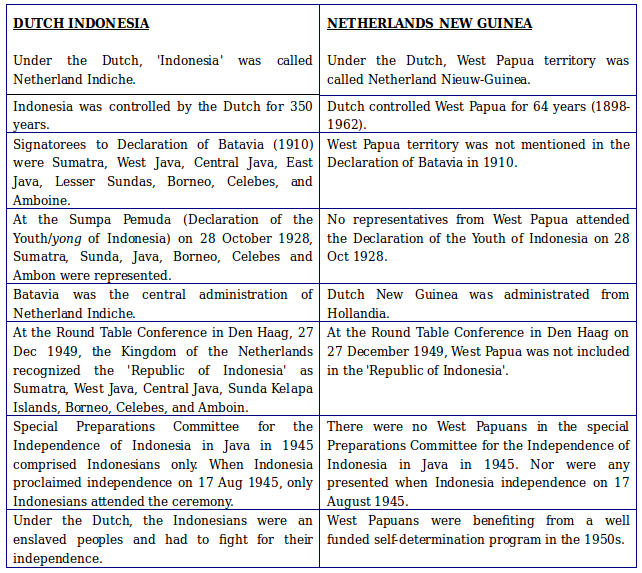

West Papua’s inclusion in Unitary Republic of Indonesia because it was Dutch colony.

Firstly, Dutch colonial policies in West Papua were different to those in the rest of the Indonesian archipelago (see table below). And secondly, if the Indonesian military-government was able to claim former colonies of the Dutch Empire like West Papua, why couldn’t it or didn’t it also claim other Dutch colonies like Surinam (in South America) Barbados (in Central America), Guinea Bissau (Africa), and colonies in South Africa?

Indonesian government utilises Lombok Treaty with Australia to abuse and isolate West Papuans

At a high-level Indonesian intelligence meeting at Ifar Gunung, the Indonesian Army Base in West Papua, on Monday 11 June 2007, the Indonesian National Parliament set up a secret intelligence operation in West Papua against the (non-violent) independence movement. Participants included the Indonesian National Defence Council, the two Military Commanders of West Papua (PANDAM XVIII TRIKORA and DANDIM), and the two Police Commanders of West Papua (POLDA and KAPOLRES).

At the conclusion of the meeting, the Police and Military Commanders were ordered to:

Issue close surveillance orders over all Papuan students at Cenderawasih University (UNCEN), Walterpos Theology College, Baptist Theology College, Isaac Samuel Kijne Theology College, DIGI Theology College, and Fajar Timur Theology College.

Monitor the student dormitories, associations, family homes, and the religious leaders of the Catholic Church, Protestant Synod, and Papuan Muslim leadership.

List the movements of every Papuan through each of the 28 regencies. Battalion 756 and the Police to stage this operation in Wamena on 8—13 June 2007.

Command ‘Anti-terrorist Detachment 88’ to list all Papuan email addresses and monitor their home computers.

At the same time (11 June 2007), Indonesian National Intelligence (BIN) agents removed at least ten Papuan leaders from their homes and put them on a Garuda flight to Jakarta. After landing the leaders were taken to a building called Wisma Sandipala nomber 34 Menteng Street, where they were interrogated and forced to name the successful West Papuans in the independence movement overseas.

Currently there are 150,000 military troops in Puncak Jaya regency, 31,000 in Timika regency, 30,500 in Wamena regency, 7,000 in Yahukimo regency, 6,712 in Pegunungan Bintang regency and 8,670 in Paniai regency. On the first week on October 2007, Indonesian Government will send three Battalion (a Battalion 320 Siliwangi from West Java and two Battalion of Diponegoro from central Java) plus 108 KOPPASUS to West Papua. In the 4th week of October 2007 the Indonesian government sent another three battalions to Papua—Battalion 303 KODAM II Lampung, Battalion 413 from Semarang and a Battalion of KODAM I Bukit Barisan, plus 108 member of KOPPASUS.

On 7 July 2007, the Indonesian government and military commanders held a ceremony to launch a militia organization called the Indonesian Papua Presidium Society (Presidium Masyarakat Papua Indonesia). The organisation is designed to counter the influence of the West Papua National Tribal Council, and authorised to continue developing the red-and-white militia in West Papua. By the end of August 2007 the organisation planned to place an Indonesian flag in every West Papuan house (which they did in East Timor before and after referendum in 1999). The Indonesian military, police and intelligence plan to increase their numbers to equal half the population of West Papua. West Papuans are currently subjected to high levels of terrorist activities, intimidation, torture, imprisonment, killing and ‘disappearances’.

For example, on 6 August 2007, Matius Bunay (twenty two years old), head of Youth at the KINGMI Church in Nabire, was kidnapped by Indonesian police and military while he was on the way home from church at 23:17. The next day his body was found in front of the gate of the local State High School.

On 8 August 2007, Martinus Degey (22 years old, student) was kidnapped by Indonesian special intelligence, and the next day his body was found in Timika.

On 9 August 2007 at 10:00 AM, Indonesia red-and-white militias, supported by the Indonesian military and police attacked, intimidated and terrorised West Papua students of the State University of Papua in Manokwari (reported by West Papua national student union base in Manokwari, West Irian Jaya).

On 10 August 2007, the Indonesian government sent 150 military personnel to Menawi village (in the district of Aggasera, Yapen regency) to assist Indonesian militias crack down on a Morning Star flag-raising ceremony. Many were detained and tortured.

On 10 August 2007, civilians in the district of Mulia (Jayawijaya regency) were gathering to pray when Indonesian military forces arrived. According to the local church reporter, 13 men were removed. Their families have not seen them since, and presume they have been killed. Their wives and children continue to be terrorised.

In the fourth week of October 2007, forty Papuans in Wamena died after Indonesian intelligence agents poisoned a container of drinking water (reported by the KINGMI Church in Wamena). The same operation was repeated in the District of Genyem (Jayapura regency).

On 17 July 2007, the Indonesian Intelligence Agency (BIN) met in Jakarta to finalise plans for killing Papuan activists with a biological agent.

Solution to the problem in West Papua

Since 2004, the West Papua National Authority has been continually advising the Indonesian government, through Section V of the Indonesian Intelligence organisation, of a feasible and legitimate solution. The government has not responded, and the situation can only be interpreted as in a state of deadlock.

The West Papua National Authority is now working with the international community to bring about talks with the Indonesian governments under the auspices of a third party. In 2007 it entered into an agreement with the Manurariki Council of Chiefs for the Vanuatu nation to reslist West Papua on the United Nations Decolonisation List (from which it was removed in 1969) thus ‘internationalizing’ what the Indonesian Republic has brutally insisted was an ‘internal’ matter for exclusive discussion between Jakarta and Jayapura.

Author:

Author: